Descrizione

PREMESSA: LA SUPERIORITA’ DELLA MUSICA SU VINILE E’ ANCOR OGGI SANCITA, NOTORIA ED EVIDENTE. NON TANTO DA UN PUNTO DI VISTA DI RESA, QUALITA’ E PULIZIA DEL SUONO, TANTOMENO DA QUELLO DEL RIMPIANTO RETROSPETTIVO E NOSTALGICO , MA SOPRATTUTTO DA QUELLO PIU’ PALPABILE ED INOPPUGNABILE DELL’ ESSENZA, DELL’ ANIMA E DELLA SUBLIMAZIONE CREATIVA. IL DISCO IN VINILE HA PULSAZIONE ARTISTICA, PASSIONE ARMONICA E SPLENDORE GRAFICO , E’ PIACEVOLE DA OSSERVARE E DA TENERE IN MANO, RISPLENDE, PROFUMA E VIBRA DI VITA, DI EMOZIONE E DI SENSIBILITA’. E’ TUTTO QUELLO CHE NON E’ E NON POTRA’ MAI ESSERE IL CD, CHE AL CONTRARIO E’ SOLO UN OGGETTO MERAMENTE COMMERCIALE, POVERO, ARIDO, CINICO, STERILE ED ORWELLIANO, UNA DEGENERAZIONE INDUSTRIALE SCHIZOFRENICA E NECROFILA, LA DESOLANTE SOLUZIONE FINALE DELL’ AVIDITA’ DEL MERCATO E DELL’ ARROGANZA DEI DISCOGRAFICI .

TAJ MAHAL

the real thing

Disco Doppio 2 LP 33 giri , columbia , CG 30619 , 1972, u.s.a.

ECCELLENTI CONDIZIONI, both vinyls ex++/NM , cover ex++

Henry Saint Clair Fredericks noto come Taj Mahal (17 maggio 1942) è un musicista statunitense.

Taj Mahal nacque a New York ma crebbe a Springfield nel Massachusetts. Suo padre era un musicista jazz e sua madre era un insegnante afroamericana.

Nei primi anni ’60 studiò agricoltura e zootecnica all’ University of Massachusetts Amherst e si diplomò nel 1964.

Dopo il college andò a Los Angeles e formò i “Rising Songs” con Ry Cooder nel 1964. Il gruppo incise per la Columbia Records

e rilasciò un singolo. Registrarono anche diversi album che non furono

rilasciati dalla Columbia Records fino al 1992. Non sentendosi

adeguatamente appagato dal suo lavoro con il gruppo decise di

intraprendere la carriera di solista.

La sua musica è di diverse derivazioni: principalmente reggae, Cajun e gospel, ma riporta anche qualche influenza di musica Hawaiiana, Africana e Caraibica.

Ha ricevuto due Grammy Awards come Miglior album blues contemporaneo: il primo nel 1997 con Señor Blues, il secondo nel 2000 con Shoutin’ in key.

Etichetta: COLUMBIA

Catalogo: CG 30619

Data di pubblicazione: 1972

Matrici😛 BL 30620-1E / AL 30620-1G /P AL 30621-1E / P BL 30621-1L

- Supporto:vinile 33 giri

- Tipo audio: stereo

- Dimensioni: 30 cm.

- Facciate: 4

- red yellow label, whiter paper inner sleeves

The Real Thing is a 1971 live album by Taj Mahal. It was recorded on February 13, 1971 at the Fillmore East in New York City and features Taj Mahal backed by a band that includes four tuba players.

Disco dal vivo inciso al Fillmore East nel

1971, “The Real Thing” è un’occasione unica per ascoltare alcuni dei

classici della produzione del grande bluesman in versioni assolutamente

affascinanti. Successivo alla pubblicazione dei tre capolavori solisti

di Taj Mahal (l’omonimo, “Natch’l Blues” e “Giant Step/Da Old Folks At

Home”), questa esibizione ci mostra una fase peculiare della sua

carriera, in cui il suo southern blues ricco di caldo soul ed

espressività da vendere si arricchiva di strumentazione non

convenzionale, testimoniando la sua curiosità per le sonorità

terzomondiste. Uno dei più carismatici personaggi della scena blues

americana in una performance strepitosa!

Track listing

All songs by Taj Mahal unless otherwise noted.

- “Fishin’ Blues” (Henry Thomas) – (2:58

- “Ain’t Gwine to Whistle Dixie (Any Mo’)” (Blackwell/Davis/Gilmore/Taj Mahal) – 9:11

- Studio recording on Giant Step/De Ole Folks at Home (1969)

- “Sweet Mama Janisse” – 3:32

- “Going Up to the Country and Paint My Mailbox Blue” – 3:24

- “Big Kneed Gal” – 5:34

- “You’re Going to Need Somebody on Your Bond” (Blind Willie Johnson) – 6:13

- “Tom and Sally Drake” – 3:39

- “Diving Duck Blues” (Sleepy John Estes) – 3:46

- “John, Ain’ It Hard” – 5:30

- “She Caught the Katy (And Left Me a Mule to Ride)” (Taj Mahal, Yank Rachell) – 4:08

- Omitted from the vinyl issue, added to 2000 CD issue. Studio recording appears on The Natch’l Blues (1968).

- “You Ain’t No Street Walker Mama, Honey but I Sure Do Love the Way You Strut Your Stuff” – 18:56

Performers

- Taj Mahal – Vocals, blues harp, chromatic harmonica, National steel-bodied guitar, five-string guitar, fife

- Howard Johnson – Tuba (BB♭, F), baritone saxophone, brass arrangements

- Bob Stewart – Tuba (CC), flugelhorn, trumpet

- Joseph Daley – Tuba (BB♭), valve trombone

- Earle McIntyre – Tuba (E♭), bass trombone

- Bill Rich – Electric bass

- John Simon – piano, electric piano

- John Hall – Electric guitar

- Greg Thomas – Drums

- Kwasi “Rocky” DziDzournu – Congas

Taj Mahal is one of those happy contradictions

of popular music. Originally a blues musician, and still essentially

one, he is nevertheless only 28 years old and a university graduate.

Though Taj is black, his initiation into the world of blues was more

through scratchy recordings than the songs relatives and neighbors sang.

The

younger generation of black blues musicians, like Junior Wells, Buddy

Guy, Otis Rush and the late Magic Sam, with whom he might off-handedly

be compared, are older than he is and the products of an indigenous

local scene (Chicago). Taj is Harlem-raised and a recent citizen of Los

Angeles.

Naturally, the differences in age, background, education

and geography manifest themselves in the music. While Junior, Buddy,

etc., play city blues, Taj plays the country blues electrified. That

is, his band does. Taj himself plays a National steel-bodied guitar,

occasionally amplified, mouth harp, banjo and fife. Junior Wells, of

course, plays harp, but harp is also frowned upon in certain young

Chicago blues circles for being too down home. And none of the young

Chicago guitarists would ever play a National.

Yet it would be

equally wrong to lump Taj with figures of the white blues revival like

Bloom-field, Butterfield and Clapton. Among these and other white

musicians, an inordinate emphasis was placed on instrumental

virtuosity; Taj is a jack of many instruments and a master of none. And

though Taj’s kind of music is more often played by white musicians than

black ones today, one can hardly call Taj’s blackness incidental. Both

his and the young white musicians’ music depend on a studied

re-creation of defunct and dying forms, yet Taj’s vocal timbre, diction

and inflection lend his performances an authenticity and authority

which many white musicians lack.

It is Taj’s combination of

earthiness and musical breadth and sophistication which enables him to

do some of his most challenging material. Not a folk artist in the

literal sense, he effectively resurrects and updates older material.

His first album, Taj Mahal, was the cornerstone of his style:

country blues of Sleepy John Estes, Sonny Boy Williamson and Robert

Johnson electrified, in both senses, by one of the most exciting bands

of the Sixties–including Jesse Edwin Davis on lead guitar and Ry Cooder

on rhythm. Its one flaw was that of a novice: in the manner of Bob

Dylan’s first album, the singing was overly exuberant and unsubtle.

Natch’l Blues

was smoother hewn, if no less compelling, and was more of a planned,

coherent album. Here, he was rewriting traditional material for his own

purposes. Out of “Corinna,” performed at various times by Joe Turner,

Roy Peterson and Bob Dylan, Taj created something entirely his own,

just as he juggled verses and generally calmed down “Rollin’ and

Tumblin'” to make “Done Changed My Way of Living.” The album was also

notable for his taking entirely non-blues songs, like the traditional

“The Cuckoo,” and giving them a blues treatment, and for his baptism

into soul music, with William Bell’s “You Don’t Miss Your Water” and

Sam and Dave’s “A Lot of Love.”

This incipient diversification reached full, schizophrenic expression on his double album Giant Step/De Ole Folks At Home. Giant Step contained a couple of pop tunes like the Goffin and King “Take a Giant Step” and “Farther On Down the Road,” but mostly it was Natch’l Blues

again, with material, this time, less carefully selected and

performances more haphazard. It can probably best be seen as the

companion to Taj’s pet project Ole Folks, a collection of ancient folk tunes sung and played by Taj unaccompanied. Ole Folks was certainly not a strong commercial concept, and Giant Step may have been tagged on as a way of justifying it. A major disappointment on the heels of Natch’l Blues, it exists in retrospect as a pretty agreeable album.

I wish I could say The Real Thing

signifies a daring new direction in Taj’s music, or a reaffirmation of

his earlier enthusiasms, but, almost by definition, it does neither. A

live album is often a way of marking time, a means of fulfilling

contractual obligations with as little sweat as possible. Taj, a while

back, dropped out of show biz and travelled to Spain, where he did some

street singing and generally took it easy. No doubt his latest musical

incarnation/creation is still gestating. The Real Thing is a

diverting, relaxed, but essentially anticlimactic record of old and

old-sounding material performed at the Fillmore East. It offers nothing

new or improved over the first two albums, and continues the artistic

limbo of the third.

The most noticeable change is the addition of

horns. Not saxes and trumpets, which would suggest some kind of soul

revue, but four tubas, with an occasional fluegelhorn or sax. This must

be Taj at his most tongue-in-cheek; the tubas, unwieldy instruments

that they are, succeed most at sounding humorous. On “Tom and Sally

Drake,” a banjo reel, a single tuba serves a structural function by

lining out the bass, but on something like “Diving Duck Blues,” from

the first album, the angularity of the basic riff is blunted by the

tubas. Because of the eccentric instrumentation and sheer number of

musicians (ten in all), some of the cuts sound disorganized even when

they are not.

The rest of the material is a mixed bag. There is

the late-hour, “Trouble in Mind”–like “John, Ain’t it Hard,” the solo

“Fishin’ Blues” from De Ole Folks At Home, and the jazzy

“Big-Kneed Gal” on which the horns fill in more predictably. “Ain’t

Gwine Whistle Dixie” has become an extended jam, during which Taj

introduces the individual band members. “You Ain’t No Street Walker

Mama, Honey But I do Love The Way You Strut Your Stuff,” occupying all

of side four, is even longer than its title. On it, Taj works out on

chromatic harmonica. I prefer Davis’ guitar-playing to John Hall’s, who

is the guitarist on this set, but the bass and drums of Bill Rich and

Greg Thomas are not surpassed by Taj’s previous sidemen.

Of

course it should be remembered that it is one thing to perform to an

audience, and quite another to play to a reel of tape. The audience at

the Fillmore that night, I suspect, walked away with a bit of the

energy which eluded the grooves of this record.

Taj Mahal (Henry Fredericks), musicista di colore nato a Harlem, figlio di un

pianista jazz di origini Giamaicane e di una cantante gospel,

laureato in veterinaria, si fece le ossa

suonando nei club di

Boston. Nel 1965 arrivo` a Los Angeles,

prese il nome del celebre tempio indiano, e formo` i Rising sons

con Ry Cooder.

Le loro registrazioni vedranno la luce soltanto vent’anni dopo su

Rising Sons (Metro Music, 1985).

I suoi interessi etnomusicali si sfogarono non tanto sul primo album

Taj Mahal (Columbia, 1967), quanto sul secondo,

Natch’l Blues (Columbia, 1969),

che faceva leva soprattutto sull’armonica di Mahal e sulla

chitarra Jesse Ed Davis,

uno dei piu` originali del “blues revival” dell’epoca.

Vi spicca la lunga Done Changed My Way Of Living, gia` tipica del

suo stile al tempo stesso affettuoso, umoristico e austero.

Invece di riprendere il discorso dai maestri di Chicago del decennio

precedente, Mahal scavo` piu` indietro nel tempo, abbracciando uno stile

arcaico e innocente, quello del country-blues e delle bande marcianti, quello

delle piantagioni e delle messe gospel.

Giant Step (Columbia, 1969) fu il suo album “rock”. Accompagnato da

una formazione elettrica, Mahal scorrazzava nel

ruggente jump-blues Give Your Mother What

She Wants e nell’aggressivo boogie Six Days On The Road.

L’album gemello De Ole Folks At Home rimane il suo capolavoro.

Dotato di una voce scura, viscerale, bruciata dall’alcool e dal sole,

capricciosa esplorazione del patrimonio folkloristico delle popolazioni

di colore, dal soul al reggae, dai Caraibi alla Louisiana,

Mahal reinventava la tradizione del Delta conferendole l’esuberanza del ragtime

e la sposava a un eclettico excursus per le strade della provincia Americana

al principio del secolo.

Tutto solo con il suo banjo, la sua armonica, la sua voce, Mahal pennella

tredici entusiasmanti foto d’epoca, dalla scarnissima e toccante malinconia di

A Little Soulful Tune, un brano-conversazione in cui si batte il ritmo

con le mani e simula l’orchestra a labbra chiuse,

al colorito assolo di banjo di Colored Aristocracy,

dal rag stranito di Blind Boy Rag all’assolo di armonica

Cajun Tune.

Era soltanto l’inizio. Di album in album Mahal avrebbe rovistato in sgabuzzini

sempre diversi per riportare alla luce i fantasmi piu` bistrattati della musica

popolare.

Su Real Thing (Columbia, 1971) impiego` un’orchestrina di nove elementi,

con tanto di tube e tromboni, per concedersi un divertissment d’autore nel

campo del jazz degli anni ruggenti.

L’album annovera altre vignette surreali in cui trasfigura la musica dei

primi decenni del secolo:

l’ironico Fishing Blues, per sola voce e chitarra,

l’incalzante jump da ballo di Sweet Mama Jamisse con le tube sguinzagliate,

e Tom Sally And Drake, pittoresco duetto fra banjo e tuba (Howard Johnson)

che incrocia bluegrass e marcia.

L’album si chiude con lo sproloquio di You Ain’t No Street Walker Mama

(quasi venti minuti).

La versione per flauto, clarinetto,

congas e orchestra di Ain’t Gwine To Whistle, rimase a lungo la

sigla dei suoi concerti.

Il suo genio si sfoga, in particolare nel periodo piu` ascetico di

Happy Just Like I Am (Columbia, 1971), con

West Indian Revelation,

Recycling The Blues (Columbia, 1972) e Ooh So Good’n’Blues (Columbia, 1973),

soprattutto negli assoli, i piu` geniali e coinvolgenti

del blues moderno; alcuni lenti e riflessivi, altri incalzanti e tribali:

quello voodoo alla chitarra acustica di Black Spirit Boogie (1971),

quello gitano alla chitarra di Gitano Blues (1972),

quello per solo canto e clapping di Free Song (1972), un vero e proprio

esorcismo collettivo,

quello country al banjo di Ricochet (1972),

quello alla chitarra di Buck Dancer’s Choice (1973).

Si ricordano poi le gag eterodosse di Cakewalk Into Town (1972), con la

tuba di Johnson, clapping e fischio, e Teacup’s Jazzy Blues Tune (1973).

Early life

Born Henry Saint Clair Fredericks on May 17, 1942 in Harlem, New York, Mahal grew up in Springfield, Massachusetts. Raised in a musical environment, his mother was the member of a local gospel choir and his father was a West Indian jazz arranger and piano player. His family owned a shortwave radio which received music broadcasts from around the world, exposing him at an early age to world music. Early in childhood he recognized the stark differences between the popular music of his day and the music that was played in his home. He also became interested in jazz, enjoying the music of musicians like Charles Mingus, Thelonious Monk and Milt Jackson. His parents came of age during the Harlem Renaissance, instilling in their son a sense of pride in his West Indian and African ancestry through their stories.

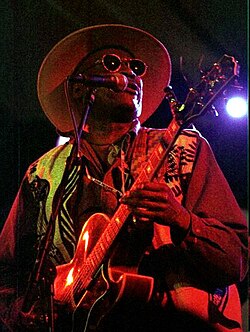

Blues musician Taj Mahal at the Museumsquartier in Vienna (Jazz-Fest Wien)

Because his father was a musician, his house was frequently the host of other musicians from the Caribbean, Africa, and the United States. His father, Henry Saint Clair Fredericks Sr., was called “The Genius” by Ella Fitzgerald before starting his family.

Early on he developed an interest in African music, which he studied

assiduously as a young man. His parents also encouraged him to pursue

music, starting him out with classical piano lessons. He also studied the clarinet, trombone and harmonica. At age eleven Mahal’s father was killed in an accident at his own construction company, crushed by a tractor when it flipped over. This was an extremely traumatic experience for him. His mother would later remarry. His stepfather owned a guitar which he began using at age 13 or 14, receiving his first lessons from a new neighbor from North Carolina of his own age that played acoustic blues guitar. His name was Lynwood Perry, the nephew of the famous bluesman Arthur “Big Boy” Crudup. In high school Mahal sang in a doo-wop group.

For some time Mahal thought of pursuing farming over music. He had developed a passion for farming that nearly rivaled his love of music—coming to work on a farm first at age 16. It was a dairy farm in Palmer, Massachusetts, not far from Springfield. By age nineteen he had become farm foreman,

getting up a bit after 4:00 a.m. and running the place. “I milked

anywhere between thirty-five and seventy cows a day. I clipped udders.

I grew corn. I grew Tennessee redtop clover. Alfalfa.”

Mahal believes in growing one’s own food, saying, “You have a whole

generation of kids who thinks everything comes out of a box and a can,

and they don’t know you can grow most of your food.” Because of his

personal support of the family farm, Mahal regularly performs at Farm Aid concerts.

Taj Mahal, his stage name, came to him in dreams about Gandhi, India, and social tolerance. He started using it in 1959 or 1961—around the same time he began attending the University of Massachusetts. Despite having attended a vocational agriculture school, becoming a member of the Future Farmers of America, and majoring in animal husbandry and minoring in veterinary science and agronomy, Mahal decided to take the route of music instead of farming. In college he led a rhythm and blues band called Taj Mahal & The Elektras and, before heading for the West Coast, he was also part of a duo with Jessie Lee Kincaid.

Career

In 1964 he moved to Santa Monica, California and formed The Rising Sons with fellow blues musician Ry Cooder and Jessie Lee Kincaid, landing a record deal with Columbia Records soon after. The group was one of the first interracial bands of the period, which likely made them commercially unviable. An album was never released (though a single was) and the band soon broke up, though Legacy Records did release The Rising Sons Featuring Taj Mahal and Ry Cooder in 1993 with material from that period. During this time Mahal was working with others, musicians like Howlin’ Wolf, Buddy Guy, Lightnin’ Hopkins, and Muddy Waters. Mahal stayed with Columbia after The Rising Sons to begin his solo career, releasing the self-titled Taj Mahal in 1968, The Natch’l Blues in 1969, and Giant Step/De Old Folks at Home (also in 1969). During this time he and Cooder worked with the The Rolling Stones, with whom he has performed at various times throughout his career . He recorded a total of twelve albums for Columbia Records from the late 1960s into the 1970s. His work of the 1970s was especially important, in that his releases began incorporating West Indian and Caribbean music, jazz and reggae into the mix. In 1972 he wrote the film score for the movie Sounder, which starred Cicely Tyson.

In 1976 Mahal left Columbia Records and signed with Warner Bros. Records, recording three albums for the record label. One of these was another film score for 1977’s Brothers;

the album shares the same name. After his time with Warner Bros.

Records he struggled to find another record contract, this being the

era of heavy metal and disco music. Stalled in his career, he decided to move to Kauai, Hawaii in 1981 and soon formed The Hula Blues Band. Originally just a group of guys getting together for fishing and a good time, the band soon began performing regularly and touring. He remained somewhat concealed from most eyes while working out of Hawaii throughout most of the 1980s before recording Taj in 1988 for Gramavision. This started a comeback of sorts for him, recording both for Gramavision and Hannibal Records during this time. In the 1990s he was on the Private Music label, releasing albums full of blues, pop, R&B and rock. He did collaborative works both with Eric Clapton and Etta James. In 1997 he won Best Contemporary Blues Album for Señor Blues at the Grammy Awards, followed by another Grammy for Shoutin’ in Key in 2000.

Musical style

Taj Mahal performing at the 1997 North Sea Jazz Festival

Mahal leads with his thumb and middle finger when fingerpicking, rather than with his index finger as the majority of guitar players do. “I play with a flatpick,” he says, “when I do a lot of blues leads.” Early in his musical career Mahal studied the various styles of his favorite blues singers, including musicians like Jimmy Reed, Son House, Sleepy John Estes, Big Mama Thornton, Howlin’ Wolf, Mississippi John Hurt, and Sonny Terry. He describes his hanging out at clubs like Club 47 in Massachusetts and Ash Grove in Los Angeles as “basic building blocks in the development of his music.” Considered to be a scholar of blues music, his studies of ethnomusicology at the University of Massachusetts would come to introduce him further to the folk music of the Caribbean and West Africa. Over time he incorporated more and more African roots music into his musical palette, embracing elements of reggae, calypso, jazz, zydeco, rhythm and blues, gospel music, and the country blues—each of which having “served as the foundation of his unique sound.” According to The Rough Guide to Rock, “It has been said that Taj Mahal was one of the first major artists, if not the very first one, to purse the possibilities of world music.

Even the blues he was playing in the early 70s — RECYCLING THE BLUES

AND OTHER RELATED STUFF (1972), MO’ ROOTS (1974) — showed an aptitude

for spicing the mix with flavours that always kept him a yard or so

distant from being an out-and-out blues performer.”

Concerning his voice, author David Evans writes that Mahal has “an

extraordinary voice that ranges from gruff and gritty to smooth and

sultry.”

Taj Mahal believes that his 1999 album Kulanjan, which features him playing with the kora master of Mali‘s Griot tradition Toumani Diabate,

“embodies his musical and cultural spirit arriving full circle.” To him

it was an experience that allowed him to reconnect with his African heritage, striking him with a sense of coming home. He even changed his name to Dadi Kouyate, the first jali name, to drive this point home. Speaking of the experience and demonstrating the breadth of his eclecticism, he has said:

The microphones are listening in on a conversation between a

350-year old orphan and its long-lost birth parents. I’ve got so much

other music to play. But the point is that after recording with these

Africans, basically if I don’t play guitar for the rest of my life,

that’s fine with me….With Kulanjan, I think that

Afro-Americans have the opportunity to not only see the instruments and

the musicians, but they also see more about their culture and recognize

the faces, the walks, the hands, the voices, and the sounds that are

not the blues. Afro-American audiences had their eyes really opened for

the first time. This was exciting for them to make this connection and

pay a little more attention to this music than before.

Taj Mahal has said he prefers to do outdoor performances, saying:

“The music was designed for people to move, and it’s a bit difficult

after a while to have people sitting like they’re watching television.

That’s why I like to play outdoor festivals-because people will just

dance. Theatre audiences need to ask themselves: ‘What the hell is

going on? We’re asking these musicians to come and perform and then we

sit there and draw all the energy out of the air.’ That’s why after a

while I need a rest. It’s too much of a drain. Often I don’t allow

that. I just play to the goddess of music-and I know she’s dancing.”

Views on the blues

Throughout his career, Mahal has performed his brand of blues (an African American artform) for a predominantly white

audience. This has been a disappointment at times for Mahal, who

recognizes there is a general lack of interest in blues music among

many African Americans today. He has drawn a parallel comparison

between the blues and rap

music in that they both were initially black forms of music that have

come to be assimilated into the mainstream of society. He is quoted as

saying, “Eighty-one percent of the kids listening to rap were not black

kids. Once there was a tremendous amount of money involved in it . . .

they totally moved it over to a material side. It just went off to a

terrible direction.”

Mahal also believes that some people may think the blues are about

wallowing in negativity and despair, a position he disagrees with.

According to him, “You can listen to my music from front to back, and

you don’t ever hear me moaning and crying about how bad you done

treated me. I think that style of blues and that type of tone was

something that happened as a result of many white people feeling very,

very guilty about what went down.”

Awards

Taj Mahal has received eight Grammy Award nominations (winning two) over his career.

- 1997 (Grammy Award) Best Contemporary Blues Album for Señor Blues

- 2000 (Grammy Award) Best Contemporary Blues Album for Shoutin’ in Key

- 2006 (Blues Music Awards) Historical Album of the Year for The Essential Taj Mahal