Descrizione

|

PREMESSA: LA SUPERIORITA’ DELLA MUSICA SU VINILE E’ ANCOR OGGI SANCITA, |

THE PAUL BUTTERFIELD BLUES BAND

east – west

Disco LP 33 giri , 1966 , this is 1983 reissue , elektra / wea italiana, W 42006, italia

ECCELLENTI CONDIZIONI, vinyl ex++/NM , cover ex++/NM

Paul Butterfield (Chicago,

17

dicembre 1942

– Hollywood,

4

maggio 1987)

è stato un armonicista e cantante

statunitense.

È stato uno dei primi esponenti bianchi

del Chicago Blues. Il suo

stile incisivo e rivoluzionario è ancora oggi un punto di riferimento

per grandi armonicisti moderni come Mark Ford e Andy Just.

Sebbene sia stato uno dei musicisti più innovativi e significativi

del suo tempo, e pur avendo suonato con personaggi del calibro di Jimi

Hendrix, John Mayall, Eric

Clapton, Stevie Ray Vaughan, Muddy

Waters, Bob Dylan, è un artista relativamente poco conosciuto.

Con la forza strumentale dei due chitarristi, East-West , secondo lavoro della Paul Butterfield Blues Band , realizzato nel 1966, desta

sensazione per il forte impatto ma anche per la presenza di due lunghi

brani, insoliti per il blues: East West, soprattutto, stupisce

per gli innesti di psichedelia, progressioni jazzistiche e scale

indiane. È uno dei dischi più importanti del blues bianco elettrico.

East-West is a 1966 album by The Paul Butterfield Blues Band which was the group’s

second full album release. The record’s title track is a long improvisational instrumental

piece inspired by blues, jazz

fusion and raga

that was considered

groundbreaking at the time of release, and over four decades later

stands out as a turning point in the history of rock and blues music. The

album contains another lengthy blues/jazz/rock instrumental in the tune

“Worksong”, which also features extended solos by Butterfield and his

bandmates.

Like the debut, the album

features traditional blues covers

and the guitar work of Elvin

Bishop and Mike Bloomfield, the latter having just

recorded Highway 61 Revisited with Bob

Dylan.

Bishop makes his recorded lead vocal debut on the slow ballad “Never

Say No”. “Mary, Mary“, written by Michael Nesmith, would later be recorded by The

Monkees.

The tune “East-West” in

music history

In 1996, former Butterfield Blues Band member Mark

Naftalin (keyboards), who recorded on the album and is pictured on

the cover of East-West, released a CD on his own ‘Winner’ label

entitled East-West Live, comprising three extended live

performance versions of the tune “East-West”. Noted music critic and

prolific author Dave Marsh contributed a substantial essay in the

liner notes regarding the historic importance of the song, both the

original 1966 recording and the live versions.

Marsh, interviewing Naftalin, notes that the tune was inspired by an

all-night LSD trip that “East-West”‘s primary songwriter

Mike Bloomfield experienced in the fall of 1965, during which the late

guitarist “said he’d had a revelation into the workings of Indian

music.”

Marsh’s expansive liner notes observe that the song “East-West” “was

an exploration of music that moved modally, rather than through chord

changes. As Naftalin explains, “The song was based, like Indian music,

on a drone. In Western musical terms, it ‘stayed on the one’. The song

was tethered to a four-beat bass pattern and structured as a series of

sections, each with a different mood, mode and color, always underscored

by the drummer, who contributed not only the rhythmic feel but much in

the way of tonal shading, using mallets as well as sticks on the various

drums and the different regions of the cymbals. In addition to playing

beautiful solos, Paul [Butterfield] played important, unifying things

[on harmonica] in the background – chords, melodies, counterpoints,

counter-rhythms. This was a group improvisation. In its fullest form it

lasted over an hour.”

In his summation, Marsh points out that “‘East-West’ can be heard as

part of what sparked the West Coast’s rock revolution, in which such

song structures with extended improvisatory passages became

commonplace.”

Going on to call the Butterfield Blues Band “one of the greatest

bands of the rock era”, Marsh concludes that “With ‘East-West’, above

any other extended piece of the mid-Sixties, a rock band finally

achieved a version of the musical freedom that free

jazz had found a few years earlier.”

- Interprete: Butterfield Blues Band

- Etichetta: Elektra / Wea italiana

- Catalogo: W 42006

- Data di pubblicazione: 1983

- Matrici : W – 42006 – BIS – A / W – 42006 – BIS – B

- Supporto:vinile 33 giri:

- Tipo audio: stereo

- Dimensioni: 30 cm.

- Facciate: 2

- Butterfly label, white paper inner sleeve

If the Butterfield Blues Band’s groundbreaking debut earned the respect

of the group’s elder influences, this one won over (and guided) the

blues boys’ psychedelic peers. Highlighted by the 13-minute-plus title

track (an Eastern-influenced jam cowritten by guitarist Mike

Bloomfield), East-West stretches the boundaries of the blues. It

would prod many lesser groups to explore, with generally dreary results,

interminable free-flight explorations. But while East-West and a

cover of jazzman Cannonball Adderly’s “Work Song” ventured in new

directions, Paul Butterfield and company remained rooted in solid

Chicago blues. East West presents the best of both worlds.

1966’s East-West, the second album from the Butterfield Blues

Band — and their last with lead guitarist Mike Bloomfield — found the

group branching out from the electric blues and adding elements of

modern jazz and the music of India, most notably on the landmark title

track, which paved the way for much of the musical experimentation of

the late ’60s.

Track Listings

Side One

- “Walkin’ Blues” (Robert Johnson) – 3:15

- “Get Out of My Life, Woman” (Allen Toussaint) – 3:13

- “I Got a Mind to Give up Living ” (Traditional) – 4:57

- “All These Blues” (Traditional) – 2:18

- “Work Song” (Nat Adderley, Oscar

Brown) – 7:53 order of solos : Bloomfield – Butterfield –Naftalin – Bishop

Side Two

- “Mary, Mary” (Michael Nesmith) – 2:48

- “Two Trains Running” (Muddy

Waters) – 3:50 - “Never Say No” (Traditional) – 2:57

- “East-West” (Mike Bloomfield, Nick Gravenites) – 13:10 order of solos : Bishop – Butterfield – Bloomfield

Personnel :

- Paul Butterfield – Harmonica

and vocals - Mike Bloomfield – Guitar

- Elvin Bishop – Guitar and vocal on “Never Say No”

- Mark Naftalin – keyboards

- Jerome Arnold – Bass Guitar

- Billy Davenport – drums

The second Butterfield album had an even greater effect on music

history, paving the way for experimentation that is still being explored

today. This came in the form of an extended blues-rock solo (some 13

minutes) — a real fusion of jazz and blues inspired by the Indian raga.

This groundbreaking instrumental was the first of its kind and marks

the root from which the acid rock tradition emerged.

Mike Bloomfield fu uno dei musicisti bianchi che cambiarono la scena

blues di Chicago. Si era fatto le ossa, giovanissimo,

nella Butterfield Blues Band (Elektra, 1965)

di Paul Butterfield, armonicista

nato e cresciuto in mezzo ai neri del South Side di Chicago.

Su quell’album storico, che diede il la` al blues revival,

Bloomfield

invento` una tecnica mai sentita prima alla chitarra, una tecnica che,

per gli assoli lunghi e insistiti e per i richiami ai raga, avrebbe

esercitato

un’influenza enorme su tutti i chitarristi successivi.

Del gruppo facevano parte i giovani Elvin Bishop e Mark Naftalin.

East West (Elektra, 1966) e` piu` sperimentale e contiene la

lunga jam

East-West, che ambiva a fondere musica nera e musica indiana

al fuoco catalizzante dell’improvvisazione free-jazz.

Questi due dischi impostarono il blues revival negli USA su basi

completamente

diverse da quelle dei complessi britannici (come John Mayall) che erano

rimasti

fermi agli anni ’50. Butterfield e Bloomfield erano cresciuti ascoltando

il

blues degli anni ’60 e presero il volo da quello stile molto piu`

elettrico e

incalzante (Buddy Guy, Otis Rush, etc).

Butterfield registro` un altro album d’eccezione senza Bloomfield,

The Resurrection Of Pigboy Crabshaw (Elektra, 1968), in uno stile

pop-jazz (David Sanborn al sax) sulla falsariga degli Electric Flag che

Bloomfield aveva appena formato a San Francisco.

(Butterfield morira` nel 1987).

Figlio di un avvocato, dopo aver studiato flauto da

giovane, sviluppò un amore per l’armonica blues, e a lui si unì uno

studente di fisica

dell’Università di Chicago,

Elvin Bishop,

anch’egli amante del blues. I due riuscirono ad entrare nel giro di

grandi musicisti blues come Muddy

Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, e Junior

Wells.

Butterfield e Bishop formeranno presto un gruppo insieme a Jerome

Arnold, Sam Lay (entrambi della band di Howlin’ Wolf) e Mark Naftalin.

Su consiglio del loro produttore discografico, i quattro aggiunsero alla

band il promettente chitarrista Mike Bloomfield, il cui lavoro ispirò l’allora ragazzino

Robben

Ford.

Nel 1963,

avverrà un fatto mai accaduto prima, e cioè che il gruppo formato da

Butterfield, che includeva anche elementi di colore, diventerà il gruppo

di casa al club Big John’s” di Chicago, club notoriamente

frequentato da americani bianchi.

La

Paul Butterfield Blues Band

La ormai consolidata Paul Butterfield Blues Band nel 1965 registra il

primo album discografico, con composizioni

proprie e classici, suonati fedelmente al Chicago Blues style

tradizionale, seppur con introduzioni stilistiche nuove ed affascinanti.

Diventano conosciuti nell’ambiente folk e blues; accompagnano infatti Bob

Dylan al Newport Folk Festival, e lì si trovano a contatto

con leggende del blues come Son

House.

Nel 1966 il batterista Sam Lay lascia il gruppo (è uscito nel 1995 un

album contenente registrazioni di classici blues con la band

originaria, The Lost Elektra Sessions), per far posto a Billy

Davenport, dal tocco più jazzistico. Con Davenport registrano East-West,

album in cui Butterfield e compagni sperimentano un nuovo sound, che

strizza l’occhio a sonorità esotiche e meno blues. Significativi sono

pezzi come Work Song e East-West, entrambi strumentali.

L’anno successivo, un nuovo cambio di formazione avviene nella band:

Bloomfield se ne va per fondare gli Electric Flag con Nick Gravenites e

Buddy Miles, e si ritroverà a suonare poi con Dr. John (Mac Rebennack) e

Al Cooper; alla band di Butterfield si aggiunge una sezione di

fiati, per emulare il sound del suo idolo Junior Parker.

Nello stesso anno esce The Resurrection of Pigboy Crabshaw,

dove Butterfield si concentra soprattutto sul canto, prediligendo un suono di armonica acustico.

L’era dei

pop festival

Con la stessa formazione suona al Monterey Pop Festival

(1967); nel 1969 partecipa al festival di Woodstock, e in quello

stesso anno si rincotra con Bloomfield e Sam Lay per registrare con

Muddy Waters l’album Fathers & Sons, con Otis

Spann al piano e Donald Duck Dunn al basso.

Passati alcuni anni, cambia nuovamente formazione e con i Better Days

registra 2 album nel 1973. Nel 1976 suona con i The Band

al loro concerto d’addio immortalato nel film The Last Waltz.

Gli anni seguenti vedono Butterfield apparire in programmi televisivi

e interviste; suona infatti con B.B.

King, Eric Clapton, Stevie Ray Vaughan e tanti altri nel concerto B.B.King:

Blues Session.

L’anno prima della sua morte esce il disco The Legendary Paul

Butterfield Rides Again .

Butterfield viene trovato morto, probabilmente a causa di un infarto

dovuto all’assunzione di droga degli anni precedenti, nella sua casa di

North Hollywood, il 4 maggio 1987.

Maturation of an idea

“I don’t lead musicians, man. They lead me. I listen

to them to learn what they can do best. That’s what gives

playing that feeling, like when you see a pretty woman and say,

‘Shit, wait a minute.’ Listening to what they do and

feeding it back to them is how any good bandleader should lead

his musicians.”

— Miles Davis on musical guidance

“I’ve got to keep people like that around because

on any given night I might play better than them, or they might

play better than me. It’s that challenge that makes

the music happen. You’ve got to read people, what’s

happening in their lives; that’s what enables you to inspire

them with your music.”

— Saxophonist David Murray on his music’s intersection

of the planned and spontaneous

And Then There Were Six

By the end of 1965 the Butterfield Blues Band had undergone the

first of a series of personnel changes that would continue on

throughout the next six years, each marking a subtle shift in

the band’s sound and direction.

When Mike Bloomfield joined in early 1965, he probably did so

with some trepidation. Butterfield was aware of Bloomfield’s

playing from his long-standing gig at the Chicago club Big John’s,

but it wasn’t until the band was about to go into the studio

to record its first effort with producer Paul Rothchild (recently

released as The Lost Elektra Sessions) that Butterfield

felt the need for a lead guitarist. Even as accomplished as he

was on guitar, Bloomfield viewed Butterfield as a musician at

another level.

“When I was around 18 years old, I had been sort of messing

around, and Paul sort of accepted me,” Bloomfield remembered

in 1968 for Rolling Stone. “Well, he didn’t really

accept me at all, he just sort of thought of me as a folkie Jew

boy, because Paul was there, and I was just sort of a white kid

hanging around and not really playing the shit right, but Paul

was there, man.”

And although their personalities might have been very different,

their dedication to the music forged a common bond. “I didn’t

dig Butter, you know. I didn’t like him,” Bloomfield

said. “He was just too hard a cat for me. But I went to make

the record, and the record was groovy, and we made a bunch more

records. One thing led to another, and he said, ‘Do you want

to join the band?’ And it was the best band I’d ever

been in. Sammy Lay was the best drummer I ever played with. Whatever

I didn’t like about Paul as a person, his musicianship was

more than enough to make up for it. He was just so heavy, he was

so much. Everything I dug in and about the blues, Paul was.”

Bloomfield’s brother, Allen, thinks “Paul fascinated

and intimidated Michael. Paul was to Michael a pretty threatening

guy, because if you screwed with him he would fight back. Mike

would use his mouth to try to avoid a problem, but Paul would

never buckle under. So Mike acquiesced to that ‘potency’

that Paul had. But he immediately recognized the virtuosity of

his playing — he was in a league with the best of the Chicago

guys. There was just an attitudinal problem between the two —

Paul was the hard ball bearing and Mike the soft marshmallow.

It took a certain period of time before Paul recognized that underneath

that veneer there was a sincerity and an earnestness. Mike had

to be the very best he could be on his ax. And when he finally

heard that, he let Michael do whatever he wanted. That was the

common denominator. He saw Mike as a player.”

By the summer of that year, any skepticism Butterfield had about

Bloomfield had dissolved, and the musical communication between

the two was obvious. “I remember sitting with Paul at a bar,

probably the Bitter End, across Bleeker Street from the Cafe au

Go-Go,” notes Mark Naftalin, “and he told me that there

was no guitarist in the country he’d rather have with him

than Mike Bloomfield. I thought the band was screaming then. The

effect of Paul and Mike mixing and matching was dizzying, and

Mike and Elvin Bishop’s guitars, when they were working together,

made a beautiful section.”

Naftalin himself became the sixth band member. Although Butterfield

and Bishop were familiar with him during his days as a student

at the University of Chicago, it was while he was studying theory

and composition at the Mannes College of Music in New York City

that he was asked to join (initiating a long relationship between

Mannes and the Butterfield bands).

“The band was in the studio working on the first Elektra

album,” he remembers, “and I came by one of the sessions,

hoping to sit in. Paul and Elvin knew me a little and had heard

me play — I used to pound it out on an unamplified acoustic

piano when they played at U. of C. twist parties, and that summer

I had sat in, or played along, with the band, once again on unamplified

acoustic piano, for a couple of sets at the Cafe au Go-Go in the

Village. On this particular day Elvin wasn’t around as the

session began, so they put the organ on his track and tried one

with me playing. This was ‘Thank You Mr. Poobah.’ The

band seemed to like the sound with the organ, and Paul asked me

to keep playing. Elvin arrived, and we shared his track. During

the course of the session Paul invited me to join the band and

to go on the road with them to Philadelphia that weekend. I accepted.”

Eight of the 11 songs on the first album, including “Thank

You Mr. Poobah,” were recorded at that session.

The band, now six pieces, was soon back in Chicago for gigs at

Big John’s for six weeks, then returned to the Unicorn Pub

in Boston. It was there that the Butterfield Blues Band began

working on a new experimental song that would alter the band’s

performances and radically expand its reputation for years to

come.

Billy Davenport and East-West

Billy Davenport started playing drums in 1939 at the age of six,

when he found a set of drumsticks in his South Side Chicago

neighborhood.

A child prodigy, he was blessed with parents that were extremely

supportive of his talents, and during the next 20 years he pursued

life as a jazz drummer in groups in high school and the armed

forces, intermixed with straight gigs with small swing combos

that played Chicago’s active jazz scene.

“I grew up on Benny Goodman and Gene Krupa,” Davenport

says. “In my neighborhood there were all kinds of clubs,

so I got to hear Billy Eckstine’s big band, Billie Holiday,

Charlie Parker — all those people. At the Persian Ballroom

— I think it was 50 cents to get in — everyone played

there.” Davenport was also very into Art Blakey and Max Roach.

“I saw Gene Ammons and once got into a jam session with Sonny

Stitt.”

But by the mid-1950s a change was underway in Chicago — jazz

was waning. “I realized around then that you couldn’t

make it in jazz unless you got with a big band. So I fell to the

blues. Like a guy told me one time, ‘Take what you know and

add to it, and it’ll come out alright.’ ”

By 1961 he was married and playing with Otis Rush. “I played

with Otis for about a year, and then I went with a harmonica player

named Little Mack Simmons, and through him I made contact with

Little Walter. I used to sit in and play with him at his gig after

I finished up with Little Mack Simmons. But Walter never liked

me too much. He said I did too many rolls — the kind of blues

he played wasn’t it.” Other gigs with Junior

Wells, Syl Johnson and again with Rush followed. “Then around

the end of 1964 I met this young man named Paul Butterfield. I

was working at Pepper’s Lounge and he’d come down and

we’d talk, but he never sat in until one Tuesday night —

jam night.”

“But it wasn’t Butterfield that got me in the band —

it was Mike Bloomfield. He came down one night, and we talked

for about an hour. He said some things were going on with the

band, and he wanted to know if I was available. I said yes, but

I didn’t know I wouldn’t like the road so much. In early

1965 they were working at Big John’s, and I sat in with the

band once, but Sam Lay was still with the band. Later that year,

after they came back from the Newport Festival, Paul and Elvin

came down — I was working with Jr. Wells — and talked

to me about playing with them. They said they were playing more

of a rock groove or swing groove. I said, ‘Call me.'”

The call came sooner than expected. Sam Lay became ill in late

1965 in Boston, and was hospitalized in Chicago. “They called

me on a Friday night where I was working at Pepper’s. They

said they were going on the road, and there was a chance to make

some real money; at that time I was making around $45 per weekend,

and the pay wasn’t working out. Paul called me about five

times that night, and we talked and I asked him one question —

could I bring my wife. Paul said, ‘You can bring your wife

or your whole family, but we need you.’ So on Monday

morning we drove up to Detroit. We rehearsed three numbers that

their drummer couldn’t do, and Paul said, ‘That’s

it. He’s the drummer.’ We left almost immediately for

Hollywood, California.”

During the Boston gig the band had started playing a long improvisation,

loosely titled “The Raga,” which was soon named “East-West.”

“We were listening to a widening range of music,” recalls

Naftalin, “including Indian classical music, particularly

that of Ravi Shankar,” which obviously impressed Bloomfield.

Soon he announced he had had a revelation with respect to Indian

music and that he understood how it worked. The band began performing

“The Raga.”

“This song was based, like Indian music, on a drone,”

explains Naftalin. “In Western musical terms it ‘stayed

on the one.’ The song was tethered to a four-beat bass pattern

and structured as a series of sections, each with a different

mood, mode and color. Every section ended with a big build-up

of eighth note accents and a climactic break. Some, but not all,

of the sections began peacefully and floated along for awhile

before building to the break. In each section the soloist chose

the mode, and throughout the song the drummer contributed not

only the rhythmic feel but much in the way of tonal shadings,

using mallets as well as sticks on the various drums and the different

regions of the cymbals.

“The first section was Elvin’s solo; he set the mood

for the piece. Starting with the second section Michael played

lead on a series of sections where he explored different modes,

or scales, some of which were suggestive of Indian or Arabic music

and some of which were North American, as in blues, country &

western or Mexican.

“In places Elvin played tamboura-like drones, especially

where Mike was experimenting with quasi-Eastern sounds. Elsewhere

Elvin played rhythm parts and counter-melodies behind Mike. In

some sections the two of them played parts that I would call

double-leads.

In the last section Paul came in with his solo, driving the tune

into the final climax, which included harmonica and guitars at

full wail and ‘Joy to the World’ on the organ in multiple

octaves, capped on occasion by a series of musical ‘amens.’

This was a group improvisation. In its fullest flower it lasted

over an hour.”

Certainly the “flowering” of East-West, and of the Butterfield

band’s expanding musical repertoire, accelerated exponentially

with the addition of Davenport, a percussionist who could

handle many styles and color and decorate long, improvised passages,

something unheard of among blues drummers. Those close to the

band, like Allen Bloomfield, heard the immediate impact Davenport

had on the overall sound and musical direction.

“Sammy Lay came from an R&B background, and as great

as he was, he was more straight ahead. ‘Mojo’ and those

songs were quite different from ‘East-West’; Davenport

was more refined, more delicate. He was very competent.

It’s possible that ‘East-West’ wouldn’t have

happened without him, because he is the source of movement in

the song. Billy was so articulate. He was a good jazz drummer

and had heard a lot of those guys, especially Max Roach. He was

just so refined.”

In the early 1950s, when Muddy Waters and other first-generation

electric bluesmen plugged in and amplified their rural blues,

there was no such thing as a “blues drummer.” Muddy

pulled Fred Below from Chicago’s jazz circles and Below’s

style set the format for blues drummers from that point forward.

Late in the ’50s Muddy brought in Francis Clay, another jazz

drummer who reinvigorated blues rhythms. Now, nearly a decade

later, Butterfield had injected the skills of Davenport, stewing

even more jazz percussion back into the mix, opening up the music

to improvisation as never before. If Below was the first great

jazz drummer in blues and Clay the second, Davenport was certainly

the third, and his playing expanded the role of drummer to even

greater heights.

“Paul never told me what to play,” Davenport says. “He

just said to play what I felt was best and try what I wanted.

I’d never heard the band when I joined, just been in a jam

with them. But when we got to California we spent a week rehearsing,

and spent a lot of time on this thing called ‘East-West.’

It took a while for me to find out what I was going to do —

it was a strange rhythm thing. I first tried to play with a jazz

beat, and that didn’t work. They kept telling me it wasn’t

a rock beat or a jazz beat, but in-between — and I didn’t

know what the hell in-between was. Then it dawned on me that there

was one thing that might work, and that was bossa nova. And that

became the pattern for what I played; it started with bossa nova,

and I turned it around some and added some things.

“Nobody was playing like that in those days.”

The Maturation of a Leader.

As the band grew and its performances began to garner rave reviews,

Butterfield was also opening up. When he started the band in the

early 1960s, his hard attitude and physical and psychological

intimidation seemed molded on the “stone leader” concept

of band leaders like Howlin’ Wolf and Little Walter. “Paul

was very temperamental,” Lay told a radio interviewer. “He

never did nothing to me, but he would go off on someone else in

the band, and I’d have to settle him down.” And as a

stone leader, Butterfield was taking a bigger share of the money.

But by the time the second Elektra album, East-West, appeared,

all that had changed. Conversation and confrontations within the

band had led to a more democratic unit, both financially and musically.

Everyone was urged to contribute. Butter was no longer always

the center of the show. Bishop and Bloomfield were both singing,

while Bishop’s musical style was allowed to grow and find

definition. At some shows Bloomfield stunned the audience by eating

fire: In 1995 Al Kooper told Bloomfield Notes that the

fire-eating was “as exciting as Hendrix setting his guitar

on fire or Townshend smashing his guitar.” “East-West,”

significantly toned down for the album, became a showpiece for

the guitarists, and a full-blown musical exploration for all involved.

Butterfield had evolved from the approach of Wolf to that of Muddy,

his mentor and great friend. Wolf was the hardened leader, barking

orders to his troops, the headliner with a back-up band. Muddy

more often took the paternalistic approach — the leader who

let his troops run with their musical abilities, the one who knew

the value of a long-time relationship between his musicians and

his music.

Butterfield, by letting go of his ego and establishing equality

in the group, unleashing his players, and by pushing his musicians

to be better while soliciting their input, was expanding the scope

of the blues band in the 1960s, much as Muddy had done with his

seminal bands of the early 1950s. His own singing and instrumental

prowess had also grown beyond that of any living harp player.

For proof, listen to The Lost Elektra Sessions, then to

East-West: On the former you hear a leader with sidemen,

on the latter a cohesive ensemble with shifting personnel in the

traditional frontman/leader’s role. Butter’s singing

is markedly different, stronger. His playing is incredible.

The Butterfield Band had become a great band– and certainly

no longer just a blues band. Butterfield was becoming a complete

musician with a very effective style of leadership. Both were

about to take on a new role they could never have imagined.

The Paul Butterfield Blues Band

was one of those rare ensembles that were soulful, charismatic and

incredibly influential. Two major players stood out as soloists in the

group; Paul Butterfield, a talented harmonica player and vocalist, and

Michael Bloomfield on electric guitar. On East West both get a

chance to display expressive originality. The contrast between

Bloomfield and Elvin Bishop’s more traditional solos are nothing short

of spectacular.

Butterfield was born and raised in Chicago’s Hyde Park neighborhood.

As a teenager, he studied flute and later developed a love for the blues

harmonica. Teaming up with the blues loving Elvin Bishop, they both began hanging around musicians

such as Muddy Waters, Howlin’ Wolf, and Junior Wells. Forming a band with Jerome Arnold and Sam

Lay and Bloomfield they began introducing the blues to a whole new

audience. The band was then signed by Elektra Records.

Butterfield and Bloomfield composed the title track East West.

This tune would create a unique shift in music history. It was more of a

jazz eastern Indian raga piece with long improvisational solos by

members of the band. At this point in time no one heard much of the

sitar in blues, but Bloomfield manipulated his guitar to create a sound

that was totally unique at the time. Butterfield complimented Bloomfield

with a distinctive harmonica sound of his own… When The Paul

Butterfield Blues Band played at The Fillmore in San Francisco in the

summer of 1966, the word spread and dozens of local bands followed in

the style of East West; helping to create the psychedelic sound

of Haight Ashbury.

East West was never commercially successful, but it was

critically acclaimed. I’ve listened to it several times lately, and

considering this album came out in 1966, it sounds fresh and unique even

today. The Paul Butterfield Blues Band was indeed revolutionary and

created a sound that emerged as the dominant rock music of the late

1960s.

Paul Butterfield (17 December 1942 – 4 May 1987) was an American

blues vocalist and harmonica

player, who founded the Paul Butterfield Blues Band in the early 1960s

and performed at the original Woodstock Festival. He died of drug-related heart failure.

Career

The son of a lawyer, Paul Butterfield was born and raised in

Chicago’s Hyde Park neighborhood.,

where he attended the University of Chicago

Laboratory Schools, a private school associated with the University

of Chicago. After studying classical flute with Walfrid Kujala of the Chicago Symphony Orchestra as a teenager,

he developed a love for the blues harmonica, and hooked up with white,

blues-loving, University of Chicago physics student

Elvin Bishop (“Fooled Around and Fell in Love“).

The pair started hanging around black

blues musicians

such as Muddy Waters, Howlin’

Wolf, Little Walter and Otis

Rush. Butterfield and Bishop soon formed a band with Jerome Arnold

and Sam Lay (both of Howlin’

Wolf‘s band). In 1963, the

racially mixed ensemble was made the house band at Big John’s, a folk

music club in the Old Town district on Chicago’s north

side. Butterfield was still underage (as was guitarist Mike Bloomfield.) Butterfield played Hohner harmonicas,

in particular the ‘Marine Band’ model, which he held in his left hand.

Butterfield Blues Band

The Paul Butterfield Blues Band was signed to Elektra Records after adding Bloomfield as lead

guitarist.

Their original debut album was scrapped, then re-recorded after the

addition of organist Mark

Naftalin.

Some of the discarded tracks appeared on the What’s Shakin LP shared with the Lovin’ Spoonful. Their self-titled

debut, The Paul Butterfield

Blues Band, containing Nick Gravenites‘ “Born in Chicago,” was released in

1965.

At the Newport Folk Festival of 1965, Bob

Dylan closed the event backed by Butterfield’s amplified band

(without Butterfield himself, however), a move considered controversial

at the time by much of the folk music establishment.

After the release of The Paul Butterfield Blues Band, Lay

became ill with pneumonia and pleurisy and Billy

Davenport took over on drums. The Butterfield Band’s second album

was 1966’s East-West.

Mike Bloomfield quit the band and formed The Electric Flag with Gravenites, and Bishop began

playing lead guitar on The Resurrection of Pigboy

Crabshaw (1967). The band now included saxophonists David

Sanborn and Gene Dinwiddie, bassist Bugsy Maugh, and drummer Phillip Wilson.

The Butterfield Blues Band played the Monterey

International Pop Festival along with The Electric Flag, Jimi

Hendrix, Ravi Shankar, and many others.

After 1968’s release In My Own Dream, both Bishop and Naftalin

left at the end of the year. Nineteen-year-old guitarist, Buzzy Feiten, joined the band on its 1969

release, Keep On Moving, produced by Jerry Ragavoy, and Rod Hicks replaced Maugh on

bass. The Butterfield band played at the Woodstock Festival, although their performance wasn’t

included in the resulting Woodstock film. In 1969,

Butterfield also took part in a concert at Chicago’s Auditorium Theater

and a subsequent recording session organized by record producer Norman

Dayron, featuring Muddy Waters and backed by pianist Otis

Spann, Michael Bloomfield, Sam Lay, Donald “Duck” Dunn, and Buddy

Miles, which was recorded and portions

released on Fathers And Sons on Chess

Records.

Better Days

Following the releases of Live in 1970 and Sometimes I Just

Feel Like Smiling in 1971, Butterfield broke up the horn band with David

Sanborn and Dinwiddie, and returned to Woodstock, New York.

He formed a new group including Chris Parker on drums, guitarist

Amos Garrett, Geoff

Muldaur, pianist Ronnie

Barron and bassist Billy Rich, naming the ensemble “Better

Days.” The group released Paul Butterfield’s Better Days and It

All Comes Back in 1972 and 1973, respectively.

In 1976, Butterfield performed at The Band‘s

final concert, The Last Waltz. Together with The Band,

he performed the song “Mystery

Train” and backed Muddy

Waters on “Mannish Boy“.

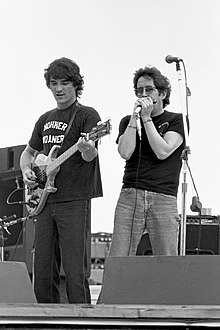

With Rick Danko, (left) on bass guitar. Woodstock Reunion,

Septenber 7, 1979

Solo

The late 1970s and early 1980s saw Butterfield as a solo act and a session musician, doing occasional television

appearances and releasing a couple of albums. He also toured as a duo with Rick

Danko, formerly of The Band, with whom he performed for the last time

in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

He also toured with another member of The Band, Levon

Helm, as a member of Helm’s “RCO All Stars”, which also included

most of the members of Booker T and the MGs, in 1977. In

1986 Butterfield released his final studio album, The Legendary Paul Butterfield Rides Again.

Harmonica style

Butterfield played and endorsed (as noted in the liner notes for his

first album) Hohner harmonicas,

in particular the diatonic ten-hole ‘Marine Band’ model. He played

using an unconventional technique, holding the harmonica upside-down

(with the low notes to the righthand side). His primary playing style

was in the second position, also known as cross-harp, but he also was

adept in the third position, notably on the track East-West from

the album of the same name, and the track ‘Highway 28’ from the “Better

Days” album.

Seldom venturing higher than the sixth hole on the harmonica,

Butterfield nevertheless managed to create a variety of original sounds

and melodic runs. His live tonal stylings were accomplished using a

Shure 545 Unidyne III hand-held microphone connected to one or more Fender amplifiers,

often then additionally boosted through the venue’s public address (PA)

system. This allowed Butterfield to achieve the same extremes of volume

as the various notable sidemen in his band.

Butterfield also at times played a mixture of acoustic and amplified

style by playing into a microphone mounted on a stand, allowing him to

perform on the harmonica using both hands to get a muted, Wah-wah effect, as well as various vibratos.

This was usually done on a quieter, slower tune.

Death

Paul Butterfield died from heart fauliure due to an overdose of drugs

on May 4, 1987

at his home in North Hollywood,

California. A month earlier, he was featured on B.B. King &

Friends, a filmed concert that also included Albert

King, Stevie Ray Vaughan, Etta

James, Gladys Knight and Eric

Clapton. Its subsequent release was dedicated to Butterfield in

memoriam.

In 2005, the Paul Butterfield Fund and Society was founded; one of

their aims is to petition for Butterfield’s inclusion in the Rock and

Roll Hall of Fame.