Descrizione

PREMESSA: LA SUPERIORITA’ DELLA MUSICA SU VINILE E’ ANCOR OGGI SANCITA, NOTORIA ED EVIDENTE. NON TANTO DA UN PUNTO DI VISTA DI RESA, QUALITA’ E PULIZIA DEL SUONO, TANTOMENO DA QUELLO DEL RIMPIANTO RETROSPETTIVO E NOSTALGICO , MA SOPRATTUTTO DA QUELLO PIU’ PALPABILE ED INOPPUGNABILE DELL’ ESSENZA, DELL’ ANIMA E DELLA SUBLIMAZIONE CREATIVA. IL DISCO IN VINILE HA PULSAZIONE ARTISTICA, PASSIONE ARMONICA E SPLENDORE GRAFICO , E’ PIACEVOLE DA OSSERVARE E DA TENERE IN MANO, RISPLENDE, PROFUMA E VIBRA DI VITA, DI EMOZIONE E DI SENSIBILITA’. E’ TUTTO QUELLO CHE NON E’ E NON POTRA’ MAI ESSERE IL CD, CHE AL CONTRARIO E’ SOLO UN OGGETTO MERAMENTE COMMERCIALE, POVERO, ARIDO, CINICO, STERILE ED ORWELLIANO, UNA DEGENERAZIONE INDUSTRIALE SCHIZOFRENICA E NECROFILA, LA DESOLANTE SOLUZIONE FINALE DELL’ AVIDITA’ DEL MERCATO E DELL’ ARROGANZA DEI DISCOGRAFICI .

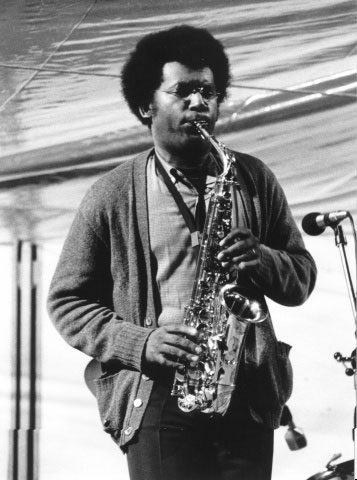

ANTHONY BRAXTON

alto saxophone improvisations 1979

Disco Doppio 2 LP 33 giri , 1979, arista records , A2L 8602 , USA

OTTIME CONDIZIONI, vinyl ex++/NM, cover ex++ , piccolo taglio orizzontale

(1,4 cm.) nell’ angolo superiore destro / short promo cut in the high right tip .

la sublime esattezza delle armonie musicali nei personalissimi ed ineguagliabili assoli algoritmici del virtuoso del sax Anthony Braxton

Anthony Braxton (Chicago, 4 giugno 1945) è un compositore, sassofonista e polistrumentista Jazz statunitense.

Definire Braxton un sassofonista jazz è alquanto riduttivo; come

compositore e musicista, ha incentrato la sua attività sul jazz

(soprattutto sul free) ma ha scritto anche per orchestra e perfino opere. Come strumentista, oltre a suonare il pianoforte, si è esibito utilizzando l’intera gamma dei sassofoni dal sopranino al contrabbasso e una grande varietà di clarinetti oltre al flauto e vari strumenti a percussione.

Supporto:vinile 33 giri

Tipo audio: stereo

Dimensioni: 30 cm.

Facciate: 4

Gatefold glossy cover / copertina apribile lucida, original lavender inner sleeves / custodie interne originali color lavanda

Brani / TracksRECORD 1 Side 1 |

- Cut One

Comp. 77 A

GNG

B-(RN)

|

R(Braxton , 7:30)

- Cut Two

Comp. 77 C

RKRR

(SMBA)

W

(Braxton , 6:25)

- Cut Three –

Red

Top –

(Lionel

Hampton / Ben Kynard , 6:13 )

Side 2

- Cut One

Comp. 77 D

KSZMK

PQ

EGN(Braxton , 7:30)

- Cut Two

Comp. 77 E

SOVA

NOUB

V-(AO)(Braxton , 4:25)

- Cut Three

Comp. 26 F

104°-KELVIN

|

M-18(Braxton , 6:30)

- Cut Four

Comp. 77 F

ATZ

GG-NOWH

KR

(Braxton , 6:19)

RECORD 2

| Side 3 |

- Cut One

Comp. 26 B

JMK-730

CFN-7(Braxton , 6:58)

- Cut Two – Along

Came Betty

(Benny

Golson , 8:00 ) - Cut Three

Comp. 77 G

VHR

G-(HWF)

APQ

(Braxton , 5:15)

Side 4

- Cut One

Comp. 26 E

AOTH

MBA

H(Braxton , 6:20)

- Cut Two – Giant Steps

(John Coltrane , 6:20 ) - Cut Three

Comp. 77 H

NMMN

TOWR

VK-N

(Braxton , 6:20)

Personnel

Anthony Braxton: alto saxophone

Produced by Michael Cuscuna

Executive Producer: Steve Backer

Recording

Engineer: Kurt Munkasci

Recorded at Big Apple Studios, New York City

Recorded on November 28 & 29, 1978, & June 21, 1979. Published

by Synthesis Music/BMI

Front Cover Art: Bonnie Singer Welton

COMPOSITION NOTES

Composition 1 [Comp. 77A] is designed to utilize

princple information in a medium fast to fast pulse continuum. The most

apparent factor that holds this work together is the nature of how given

idea fragments are mashed together in a somewhat reverse development

situation. The dynamics of this piece also utilize extreme intervallic

leaps—which is to say, the idea construction of this work is both varied

and complex in that the actual ‘stuff’ of the music has nothing to do

with development but instead deals with the constant collision—or in

most cases interruption—of fragmented constructions. The principle

working tools which underlie how this process works can be reduced to

(1) intervallic phase fragments and (2) accented eighth note movement

figures. There are three time units in this movement—fast—medium slow

(with the use of more silence)—and medium fast. The extended use of this

approach also finds the use of melody—like related material in

juxtaposition to reverse development and thrust projected materials

(constructed as to give the impression of more than one instrument).

This composition is dedicated to the composer Ulysses Kay.

Composition

2 [Comp. 77C] is a work designed to deal with the dynamic possibilities

of a major third diatonic phrase (ie. CDE, DEF, EFG, etc.). This

version can be broken into three sections—original position, extended

position, and mixed position. Original position is only the basic use of

this principle in its normal diatonic state— with the added possibility

of changing keys whenever desired. The extended position of this

technique has to do with the modification of some aspect of its

use—which in this improvisation was an intervallic separation. The mixed

position of this technique utilizes the same ‘germ figure’ with the

added use of melodic material—that is, improvisation utilizing melodic

organization and conventional development.

This composition is dedicated to my friend Barbara Mayfield.

Composition 3 [Comp. 77D] was conceived as a work to utilize the

possibilities of slap tongue technique and can be broken into three

distinct compositional areas. The first area utilizes short multiphonic

phrases as a tool for establishing focus on slap tongue possibilities

(which in this case are against short pianistic phrases). The second

section utilizes multiphonic massed configuration movements with the use

of slap tongue technique as an integral factor in shaping attack. The

third section utilizes multiphonic phrase movement against ultra high

sound figures—with the added use of instrument sounds as a color factor.

Throughout the composition there is the added ingredient of vocal

intermixture—added to both given multiphonic chords or as an integral

factor in a given phrase-patch.

This composition is dedicated to my friends Emilio and Pat Cruz.

Composition

4 [Comp. 77E] is built from five notes (G, Ab, C, D, Eb) basically and

was designed as a vehicle to make a shakuhachi type music. (I have long

been interested in this kind of approach.) There are three basic

treatments in this version, one—the basic statement of material with

respect to the five note row, two—the use of this same concept with the

addition of circular breathing and three—the fragmented use of given

figures. This composition was also constructed to utilize a more

accented vibrato in given sections, and also half tone and micro tuning.

As an improvisor this composition presents a special challenge in that

its reality is not separate from world culture and as such, this work

represents a new beginning to solidify a wider basis for working

material—for me that is.

This composition is dedicated to the dancer Sheila Raz.

Composition 5 [Comp. 26F] is based on the concept of a repetition

continuum. That being the use of repetition and the gradual change of

events by either adding a given element to the basic idea scheme or

taking away a given element. The range of material in this version can

be separated into several categories—simple configurations, having to do

with an idea built from one or two notes—multiple configurations, ideas

that are constructed from several different figures and shape

configurations, that being shapes which serve as generating

considerations for repetition. The use of dynamics must also be

considered a principle factor in this composition, for the nature of how

a given figure is set up dynamically determines whether or not its

transformation can be successful. The nature of a given idea

transformation also necessitates the use of link structure elements—that

being the modulation of given aspects of a principle idea structure.

This composition is dedicated to the composer Phillip Glass.

Composition

6 [Comp. 77F] is basically an open-ended ballad. By open-ended I mean

the improvisation is not based on either chord changes or a

predetermined time structure but instead extends freely with respect to

the stated melody at the beginning of the work. The theme at the

beginning is not a constructed melody in a completed sense but rather a

set of figures which can be used in several ways for improvisation. This

particular version utilizes an increased spacial arena—from (if numbers

one to ten could represent a tempo-pulse parameter) a velocity of

three-to-one-to-three. The structure of improvisation in this version

accents the register of a given idea alignment. That is: the opening

improvisation is in the middle register of the saxophone

and is played at a mezzo forte—the middle section is played in the low

register at a pianissimo—and the third section is high register at a

forte.

This composition is dedicated to my daughter Terri.

Composition 7 [Comp. 26B] is constructed to deal with the dynamic

possibilities of staccato long and short sound movements. The first

treatment utilizes changes in intervals as a reality factor and is the

primary shape (the staccato short sound in this context is also the

principle language factor as well). The second treatment for this

principle utilizes the long staccato sound in an extended

context—establishing the reality of the idea but functioning as one

ingredient among many. The third use of this principle is staccato

permutated type ideas which maintains the basic focus of constructed

elements but not in a dominant manner. The extended use of this approach

also finds the use of melodic related like material put in

juxtaposition to reverse development. Again, in this work there is no

development as such, rather the natural continuance of its design moves

to utilize principle material in as many ways as possible—(for its

moment improvisation).

This composition is dedicated to the saxophonist and composer Kallaparusha Difa.

Composition

8 [Comp. 77G] is based on the whole tone scale and utilizes the eighth

note as the primary language factor. There are three basic treatments in

this particular version and each treatment differs only with respect to

its tempo. The first section is medium to medium slow, the second

section is fast, and the third section is medium slow. The basic

phrasing of this work utilizes a more legato type connection between

events. This particular approach gives only three possibilities for

treatment—diatonic postulation, harmonic or chordal postulation (that

being the use when possible of major third and augmented fifth patterns

in a given idea formation) and scale changing (going from one whole tone

scale to the other and back). The actual continuum of this work does

utilize conventional type development—(ie. from idea to idea a given

expansion was executed with respect to what preceded it).

This composition is dedicated to the birth of my son Tyondai.

Composition 9 [Comp. 26E] utilizes intervallic shifts as a means to

establish its working language. By intervallic shifts I am referring to

the execution of a given figure in several registers of the

instruments—or in several permutations. The secondary working language

of this work are multiphonic sound block configurations with the added

use of voice material. In the principle language, dynamics are used in a

somewhat extreme manner as a means to establish the rotation of events

from interval to interval. The continuum of events in this work should

not be viewed as variation but instead expansion as a means to isolate

given aspects of its idea base.

This composition is dedicated to the multi-instrumentalist composer Karl Berger.

Composition

10 [Comp. 77H] is designed to deal with the dynamic possibilities of

trills. This work utilizes several types of trills—from the chromatic

and diatonic trill, to the intervallic trill, to the extreme intervallic

trill. This version is constructed in three principle sections and each

of these versions can be viewed with respect to its tempo function.

That being, the first section is slow, utilizing chromatic and diatonic

trill possibilities in a ballad like context, the second section is

faster with a more extreme use of trill material—and the third section

utilizes the trill in a more integrated phrase context. The actual

progression of events in this work are conventional as far as idea

sequencing is concerned—although there is no theme as such.

This composition is dedicated to the birth of David Aaron Weltin to my friends Hans and Bonnie Weltin.

This double-Lp features Anthony Braxton

playing his strongest horn (alto-sax) unaccompanied on ten of his

diverse originals plus a trio of standards (“Red Top,” “Along Came

Betty” and “Giant Steps”). The thoughtful yet emotional improvisations

contain enough variety to hold one’s interest throughout despite the

sparse setting; this twofer (as with many of Braxton’s Arista recordings) is long overdue to be reissued on CD.

En el campo de la improvisación, sobretodo en el que Braxton se

desenvuelve – ese de la garra, del feroz despliegue de recursos y un

opido envidiable – me dejo llevar simplemente hasta no ver fondo de

botella. Braxton tenía sus aptitudes musicales en su punto más alto en

1979. El aire no se le acababa tan fácilmente y su soltura para

improvisar le impedía repetirse constantemente. De hecho, a cada

composición, le suceden proezas de la música cruda y con variantes

tonales que se asumen como revisiones a su propia locura interpretativa.

Rudos repasos a la siempre fiable habilidad de Braxton en cada

composición, que no solo cumplen un papel de tour de force en su

capacidad de improvisar, también son una guía tosca al papel de

explorador de sonidos de los instrumentos de viento que le provocan a

uno hasta dolor de cabeza al tratar de echarse completo el disco.

Pues quepa la advertencia, este disco no se traga tan fácil, pero

dándole unas cuantas repasadas se profundiza en ese sonido agresivo y

bello a la vez, atrapado en la necesidad de sonar y retumbar en

cualquier lugar que se escuche.

PD: Sus enfermizas variantes a Giant Steps y Along Came Betty son simplemente épicas.

Nato e cresciuto nel South Side di Chicago, studia sassofono con Jack Gell, al tempo insegnante anche di Henry Threadgill.

Nel 1963 si iscrive al Wilson Jr. College e poco dopo parte per il

servizio militare; nel 65 è in Corea dove suona con la banda militare e

ha modo di improvvisare con musicisti Coreani.

Nel 1966, appena tornato a Chicago, diventa membro della neonata AACM (Association for the Advancement of Creative Musicians).

Inizia a suonare in gruppi formati da musicisti dell AACM e forma

propri gruppi con Leroy Jenkins, Thruman Baker Leo Smith ed altri.

Inizia anche a esibirsi in solo: questi saranno concerti importanti per

il futuro sviluppo del suo linguaggio musicale.

Nel 1967, sotto l’ala protettiva di Muhal Richard Abrahams che lo vuole al suo fianco per la registrazione del suo Levels and Degrees of Light, entra per la prima volta in una sala d’incisione, già nel marzo del 1968 Braxton è pronto per registrare il primo album a proprio nome: il seminale e programmatico fin nel titolo, Three Compositions Of New Jazz insieme ai fidati Leroy Jenkins e Leo Smith.

Nel 1969 la francese BYG invita i musicisti dell’AACM a Parigi,

Braxton partirà per Parigi nel giugno di quell’anno ma prima avrà modo

di incidere per la Delmark altri due album capitali: l’album per solo

sassofono “For Alto” (probabilmente il primo album interamente per sax

solo) e il disco (a lui intestato ma di fatto cooperativo) con Jenkins e

Smith Silence.

I pezzi di “For Alto” portano dediche, tra gli altri, a Cecil Taylor e John Cage

un disco in solo per uno strumento melodico quale il sax contralto

diventerà, per motivi ideologici e ancor prima economici, negli anni a

venire una prassi diffusa. Tra coloro che negli anni settanta (e anche

dopo) si dedicheranno in maniera più convinta (e convincente) alla

performance solistica non si può non citare Steve Lacy.

Partito, insieme a diversi altri musicisti dell’AACM, per Parigi “in

cerca di fortuna” con un biglietto di sola andata, Braxton tornerà a

Chicago nei primi mesi del 1970, nel frattempo in Francia avrà modo di

documentare la sua musica con due album a proprio nome e diverse

collaborazioni.

Poco dopo il rientro negli USA (1970), Braxton entra in contatto con Chick Corea (piano), con il quale insieme a Dave Holland (basso) e Barry Altschul (batteria) forma il gruppo “Circle“.

Il quartetto ha vita breve, nonostante i numerosi ingaggi sia negli USA

che in Europa, ma Grazie a Circle Braxton ha modo di farsi

ulteriormente ascoltare e conoscere e può, nel frattempo, continutare ad

esibirsi in solo. Se Corea lascia il quartetto per più remunerativi

approdi, Holland e Altschul rimangono fedeli a Braxton e costituiranno

la base dei suoi più importanti gruppi degli anni a venire.

Nei ritagli di tempo, rubati al quartetto Circle, Braxton continua a

documentare, in Francia Inghilterra ed altrove in Europa la sua musica

in solitaria o con gruppi diversi. La documentazione discografica della

musica di Braxton nei primi anni settanta è quasi esclusivamente

europea. Sarà solo nel 1974 con la firma di un contratto pluriennale per

l’Arista che Braxton tornerà ad incidere stabilmente in America. Il

primo disco del contratto, inciso alla fine del 1974, si titolerà “New

York Fall 1974” con Holland (contrabbasso) e Wheeler (tromba) e Jerome

Cooper anziché Atschul alla batteria. “New York Fall 1974” è insieme un

disco nodale ed estremamente variegato: in un brano suona in duo con le

elettroniche di Richard Teitelbaum,

in un altro chiama a se il futuro World Saxophone quartet. Nei mesi a

venire, grazie anche ad una maggiore serenità economica, Braxton

riuscirà ad riunire stabilmente un quartetto che, con lievi ma

significative varianti, lo accompagnerà per buona parte degli anni

settanta. Il primo quartetto verrà documentato compiutamente in uno dei

punti fermi della prima fase della carriera Braxtonia, (e di tutti gli

anni settanta) il fondamentale “Five Pieces”, secondo disco inciso per

l’Arista.

In quegli anni, Braxton registra anche duetti con George Lewis (lo splendido “Elements of Surprise” dal vivo a Moers) e con Richard Teitelbaum al sintetizzatore.

I potenti mezzi dell’Arista gli permettono di incidere due suoi

progetti, anche economicamente, impegnativi si tratta di “Creative

Orchestra Music”e “For Four Orchestras”.

Nel corso degli anni 80 e all’inizio degli anni 90, il gruppo regolare di Braxton fu un apprezzato quartetto con Marilyn Crispell (piano), Mark Dresser (basso) e Gerry Hemingway (batteria).

Braxton ha collaborato con decine di musicisti, tra cui Derek Bailey, Evan Parker, Globe Unity Orchestra, Max Roach, Mal Waldron, Dave Douglas, Ornette Coleman, Dave Brubeck, Lee Konitz, Peter Brötzmann, Willem Breuker, Muhal Richard Abrams, Steve Lacy, Roscoe Mitchell, Pat Metheny, Frederic Rzewski, Ursula Oppens.

Dal 1995

le composizioni e le esibizioni di Braxton riguardano interamente

quella che egli chiama “Ghost Trance Music” che consente la performance

simultanea di un qualunque numero di suoi pezzi.

Braxton ha studiato filosofia alla Roosvelt University. Dopo avere insegnato al Mills College è ora professore di musica alla Wesleyan University di Middletown (Connecticut) per le cattedre di composizione, storia della musica e improvvisazione. Nel 1994, Braxton ha ottenuto la MacArthur Fellowship.

La musica di Braxton

Dal punto di vista musicale Braxton è stato influenzato da Warne Marsh, John Coltrane, Eric Dolphy e, non ultimo, il suo prediletto Paul Desmond, ma anche da compositori contemporanei come Karlheinz Stockhausen, John Cage e Arnold Schoenberg.

La musica di Braxton è sorretta da un sostrato teorico nutrito: egli è

l’autore di diversi volumi nei quali spiega minuziosamente le proprie

teorie ed i principi su cui si basano le proprie composizioni: “Triaxium

Writings” (in tre volumi) e “Composition Notes” (in 5 volumi) entrambi

editi da Frog Peak Music.

Per quanto le sue composizioni siano decisamente di avanguardia, alcune

caratteristiche (soprattutto lo swing e la ritmica) mostrano radici che

affondano nel bebop di Charlie Parker.

I pezzi di Braxton hanno spesso per titolo dei simboli grafici ed

hanno costituito, e tuttora costituiscono, uno degli aspetti criptici

della musica e personalità di Anthony Braxton.

Anthony Braxton

Alto Saxophone Improvisations 1979

ANTHONY BRAXTON Alto Saxophone Improvisations 1979

Arista A2L 8602 (2-LP)

LINER NOTES

In the summer and fall of 1978 I had the opportunity to tour America and Europe performing solo music for the alto saxophone.

The route of these performances included such diverse places as

Boulder, Colorado; Austin, Texas; San Francisco as well as Vienna and

Central Europe. The challenge of performing so many solo concerts in one

period represented a new experience for me–normally my solo

performances are few and far between (averaging at most one or two

concerts every other month) and I was able to learn a great deal from

this opportunity. The past couple of years have seen many changes

reshape world creativity. Of those changes, certainly the dynamic

acceleration of solo activity can be viewed as a major factor

responsible for the expanded reality of present day creative music. The

reality implications of this phenomenon are clear; for the emergence of

solo activity increases the dynamic spectrum of individual

participation–and this is true on many levels. The progressional

continuance of this period has now seen the forming of a new kind of

creative musician–whose activity transcends any one criterion and whose

scope cannot be limited by superficial boundaries concerning whether or

not a given participation is ‘correct’ or ‘legitimate.’ In actual terms

we can now experience a spectrum of solo musics involving every kind of

instrument–this is true whether we are focusing on the saxophone,

guitar, trumpet, trombone, etc. I believe these changes represent a

positive advancement for world creativity, and a signal as to what the

future holds. My involvement with solo activity can be broken down into

several categories: one, the development of an alternative language pool

for improvisation (which for the past twelve years has involved

utilizing the altosaxophone as a separate tool for exploration); two,

the development of a body of solo music that utilizes improvisation only

in its infra-structure (a music comprised of 50% written material and

50% open material for every kind of instrument); three, the use of

traditional material in a solo context (involving the use of material

from every sector and time zone of earth music, from rags and bebop to

Western Art Music to Tibetan Music); four, the development of a body of

works for the creative multi-instrumentalist (that being a solo music

which would allow, and plan for, the use of several instruments and/or

medias in a given performance—including percussion and choreography);

five, the development of a series of completely notated works and six, a

more extended view of solo activity. All of these categories, and

hopefully new ones as well, will determine the reality of solo music as

we move to the next cycle. I believe we are now on the threshold of a

major vibrational and reality change in earth creativity and life. The

progressional emergence and participation of solo creativity will be

important for how it will clarify the nature of alternative creative

expansion.

In 1967 as a means to explore improvisation and composition I moved to

dissect the components of music methodology into several areas for

alternative investigation. At the time I referred to my approach as

‘conceptual grafting’—since the essence of this viewpoint involved

isolating various factors as a means to build a music from particular

parts, and this approach has underlined the route my work has since

taken. By ‘conceptual grafting’ I meant that a given composition could

be put together based on the integration of particular elements—as

opposed to the nature of its harmonic or thematic reality. In fact, the

reality of conceptual grafting would have nothing to do with

conventional harmony nor would there necessarily be a theme in the way

we have come to view this word. Instead this approach would move to

clarify the dynamic implication of ‘principal elements.’ The best

example to understand this approach would be to imagine painting a

picture with only blue or with only green, or better still with mostly

blue but with isolated touches of red and brown. The essence of

conceptual grafting is this and nothing more—that is, an attempt to

develop alternative considerations for participating in the creative

process, based on the reality of its ‘working ingredients.’ For the most

part, all of the material on this record can be viewed as representing

the first category of my involvement with solo music and as such the

basic focus of this essay will attempt to clarify just what this

approach is. The fact is, the reality of my solo music has served as the

basis of my total approach in creative music—and this is especially

true for how I have come to utilize improvisation. This can better be

understood by viewing the dynamic implications of the post Coleman and

Taylor juncture of the music in the sixties. For the information scan of

creative music in this period would transcend the nature of how

functionalism was perceived and practiced from the forties on thru to

the fifties. The dynamic implications of Coleman, Taylor and Coltrane’s

activity (among others) would exhaust the traditional application of

harmony rhythm and structure, and in doing so also establish the nature

of alternative investigation for the next generation of creative

musicians. My attempts to solidify an alternative methodology is a

direct response to what this development posed for both myself and for

expanded functionalism. For the expanded implications of post Ayler

creativity is not one dimensional but instead gives insight as to the

total reality position of alternative functionalism—as manifested in the

reality of creativity and/or composite information dynamics. With this

in mind, the accelerated continuum of alternative creativity must be

viewed for what its emergence will pose to the composite reality of

information dynamics and ‘particulars’—and will not be the work of any

one person but will solidify, in its nature state, as a result of the

work of many people. With this in mind, I offer my work as one approach

among many. The use of conceptual grafting has moved to give another

understanding of creative dynamics and information focus. For the

solidification and practice of this technique has helped to clarify my

understanding of alternative functionalism and/or musical language.

Moreover the reality of this technique has also moved to shape my own

improvisational vocabulary in other contexts as well. At present the

reality of my ‘working instrumental vocabulary’ has to do with the

extended use of conceptual grafting as an isolating factor for ‘idea

construction.’ In other words the dynamics of my participation in

creativity is not simply about ‘expressing myself’ as this is understood

in existential terms (as I am becoming less and less interested in

myslef in that position) instead, since the middle sixties I have moved

towards constructing a re-systemic viewpoint that clarifies the reality

dynamics of alternative methodology—with respect to the implication of

basic elements and reconstruction. By attempting to isolate and utilize

fundamental material in this manner, I have become interested in gaining

insight as to the composite implications of principle source

information–and what this could positively mean for transformation. The

essence of my work in this context can be viewed with respect to what

it raises about alternative functionalism, rather than what it signifies

about any one individual (although I have not meant to imply that this

technique is of no value for the individual). In other words, the

extended implications of a given mixture of elements transcends the

dynamics of any one person (which is to say, a given mixture of source

ingredients does produce a particular effect on any person experiencing

that mixture—no matter who is playing). All of the compositions on this

record—with the exception of the three pieces I have included from the

traditional repertoire—can be viewed with respect to the nature of its

use of conceptual grafting. For the dynamics of this principle do not

move to solidify one kind of music but instead help to differentiate one

procedure from another. Each composition on this record is built up

from a separate mix of elements—which is to say,

improvisation in this context is not simply about playing whatever seems

to be appropriate for the moment but rather ‘invention with respect to

the nature of its ingredients and the added demands of its schematic.’

What you have here is not a music designed for open improvisation rather

the technique of conceptual grafting can be viewed as an elastic

approach to composition. As such, the actual music on this record can be

viewed as one example of a particular mix—with the understanding being

that not only are other versions possible, but also other versions by

different musicians. The nature of a given ‘mix’ of material in this

process can be viewed in much the same fashion as one views chord

changes in traditional music. For the reality of a particular

interpretation must not only respect the principle ingredients of its

given mixture, but also the progressional sequence or ‘nature of

treatment’ of its components. As such, all of the material in a given

composition is dictated as well as how that material is to be treated

(or at least how a given principle is to be executed either technically

and/or conceptually). The challenge then for the creative musician is to

function from a given set of coordinates and actualize ‘it.’ This

approach can again be transferred to painting in the sense of making the

decision to paint a given picture using only blue as the principle

color—with red and brown for particular shapes–and basically choosing

to work from given shapes—like maybe deciding to use the ‘circle’ as the

primary shape and the ‘square’ as a secondary shape. In the final

analyses the concept of conceptual grafting gives insight as to the

reality of decision making— and the dynamic implication of

‘principle-material.’ The reality of conceptual grafting can be viewed

on several levels, for the dynamics of this approach is not limited to

any one region or information focus. Instead the continuum of this

forming methodology will address itself to both the implications of

re-functionalism and the particulars of spiritual designation. In other

words the dynamics of principle material is not separate from its

spiritual implications and its physical universe effect—and yet I do not

present this viewpoint as something new in itself, because it isn’t.

The fact is, the extended spiritual significance of information and

principle fundamentals has long been understood and practiced in world

culture (ie. Africa, India the American Indian, Tibet and the East) and

has only been subjected to dynamic confusion in the last five hundred

and some years in the West. There is now the need for new attempts to

deal with extended methodology—in all of its dynamic aspects

(encompassing the functional implications of a given system as well as

the vibrational and spiritual implications related to that system). Yet,

I am not proposing that the emergence of conceptual grafting will solve

this most complex problem—for the particulars of planet reconstruction

will involve much more than the dynamics of a given technique—but I can

say this approach has greatly clarified the route my own creativity has

taken. The basis of this approach has moved to give an alternative view

of principle material and reconstruction, and this information can be of

value in the search for the solidification of a complete alternative

methodology (and viewpoint). I see the technique of conceptual grafting

as only one factor in this resolidification—serving more in this period

as a foundation for extended investigation than a complete viewpoint.

The solidification of this approach in the middle sixties established

the nature of my involvement with creativity on many levels that I am

only now beginning to understand. In the beginning conceptual grafting

was only a tool I utilized for musical analyses—as a means to gain

insight into the music of my early influences—later, this same technique

would provide the basis for establishing my own creative viewpoint. As

such, the technique of conceptual grafting has helped me transcend the

reality of post-Webern organization and/or John Coltrane saxophone

licks, by providing a context for examining the dynamics of methodology

(that being—how given musical situations are formulated, and the

importance of understanding musical language). The realness of this

technique would clarify the dynamics of ‘principle working elements’

without imposing an empirical system separated from real spirituality.

In accepting this disciple the progressional reality of my activity has

become increasingly clear—that being: the reality of my work can be

viewed as an investigation as to the metaimplications of principle

formation—as it pertains to the dynamic fundamentals which solidify what

a given information line means in its expanded sense (its actual

physical universe effect as well as its spiritual assignment) and what

this implies for the formation of a possible alternative world music. As

such, to investigate the reality of various disciplines is to move

towards gaining insight as to the multi-implications of transformational

methodology—and what this poses for the dynamic cosmic factors which

dictate principle information. I have chosen this route because I

believe that the reality implications of creativity are directly related

to the progressional continuance of search life—and positive change. In other

words creativity is about something—and is not separated from the

fundamental laws that govern the composite universe. The nature of this

period in time has necessitated that this ‘something’ be investigated

and vibrated to, on as many levels as possible; and yet I have not meant

to construct a wrong impression about my viewpoint. In the final

analysis, I have chosen the route which makes the most sense for

me—which is to say, my work has not solidified because the universe has

necessitated that I come forth to save the planet. Rather I have moved,

like all of us, towards that which is most real to me—with the hope that

something of positive value can also come from what I am interested in.

I have included three compositions from the tradition on this record as

a means to have the widest possible spectrum of material. Each of the

compositions was chosen because of the nature of its particular

dynamics— that being, a blues from the tradition, a richly constructed

harmonic composition and a super harmonic structure from John Coltrane’s

third period. The use of traditional material in this context moves to

open new possibilities for treatment. Not only is there no piano voicing

chord positions but the rhythmic aspect of the music can also be shaped

more with respect to the nature of a given idea construction. As such, I

have regularly included standard material in my solo concerts (at least

for performances involving the use of material from category one

initiations) both as the color consideration, and as necessary material

in its own right. Finally it is important that the concept of conceptual

grafting be viewed in its most real context. In other words, I have not

simply constructed an organizational approach that has precedence over

the actual ‘isness’ of the music. Rather, the concept of conceptual

grafting was conceived as an alternative means to approach creative

organization and/or conceptual material. The challenge for the creative

musician is to make a given integration of elements ‘live.’ In other

words, the primary focus of the music is not on the ‘how’ but on the

‘is’—this is true whether the approach is perceived as traditional or

extended. Anthony Braxton ’79

“Sono interessato allo studio della

musica, alla disciplina della musica, all’esperienza della musica e alla

musica come un meccanismo esoterico per continuare sulla strada delle

mie reali intenzioni…”

“Volevo un sistema tale da essere

paragonato alle dinamiche della curiosità. Volevo avere una musica dove

poter trovare divertimento”

“La parola musica indica una

convenzione per definire ciò di cui mi occupo ma, solitamente e in molti

modi, essa indica una limitazione”

Quando fa il suo esordio

nel mondo della musica afroamericana, Anthony Braxton ha 23 anni, è il

1968 e il fondatore dell’AACM di Chicago (Association for the

Advancement of Creative Musicians), Muhal Richard Abrams, lo chiama per

la registrazione del suo capolavoro, “Levels And Degrees Of Light”. Il

suo stile è ancora leggermente acerbo, ma lascia già intravedere tutte

le potenzialità espressive che di lì a poco troveranno una prima,

decisiva conferma in quel “3 Compositions of New Jazz” che, insieme a

“Sound” di Roscoe Mitchell è da considerarsi come il big bang di tutto

l’avant-jazz a venire. Uno scardinamento delle strutture e un

ampliamento degli orizzonti, con tanto di sconfinamento nell’avanguardia

europea che farà epoca. E, intanto, già l’idea di utilizzare diagrammi

(nel solco delle “formule” di Webern e Stockhausen) al posto dei

semplici titoli delle varie composizioni: diagrammi che definiscono il

campo d’azione dei vari musicisti, quasi fossero spartiti scritti in

caratteri matematici. Molti di questi diagrammi restano, comunque, del

tutto imperscrutabili e, come se non bastasse, finiscono per intersecare

concezioni misticheggianti che davvero danno il senso di un’artista

eccentrico, soggetto a crisi depressive, ma anche, di rimando,

estremamente produttivo, anarchico, iconoclasta, inafferrabile. Un

giocatore di scacchi, anche. E questa potrebbe dirla lunga, se solo

avessimo un attimino l’immaginazione in stato di grazia…

Le

idee radicali che Braxton inizia a sviluppare in “3 Compositions Of New

Jazz” si basano su di una visione “controllata” dell’improvvisazione,

che ha come punti nodali la filosofia e la matematica, due concetti non

convergenti, ma complementari. La prima, infatti, consente all’uomo di

“vedere oltre”; la seconda, invece, è ciò che quell’”oltre” cerca di

organizzarlo. Inoltre, quel suono di tipo “cameristico” evidenziava

anche l’inclinazione braxtoniana per le idee di Lukas Foss, il

compositore americano fondatore nel 1957 di un gruppo da camera che

utilizzava un tipo di improvvisazione proprio di tipo “controllato”,

ovvero basata su procedure di variazione prestabilite. Ebbene, se

Braxton riprese queste idee, man mano le rese così personali (si vedano

anche lavori come “B-Xo/ N-O-1-47A” e “This Time”) da indirizzarle verso

un’idea di improvvisazione in solitaria che doveva suscitare clamore ed

innescare una vera e propria rivoluzione con la pubblicazione

dell’epocale “For Alto” (1968).

“Penso costantemente alla distanza che separa la musica com’è dalla musica così come dovrebbe essere”.

Primo

disco per solo sax della storia (in precedenza c’erano stati solo

tentativi “sparsi”, tra i quali quelli di Coleman Hawkins ed Eric

Dolphy), “For Alto” sconvolge la sintassi di uno degli strumenti più

importanti della musica jazz (il che, poi, di rimando, significava

andare ad intaccare la stessa sintassi della musica afro-americana),

utilizzando il silenzio come un vero e proprio tassello musicale (“To

Composer John Cage”), scrutando il baratro da cui il rumore getta la sua

luce più ambigua e riallacciandosi ad Albert Ayler nei quasi venti

minuti di “Dedicated To Multi Instrumentalist Leroy Jenkins”, in cui la

“poetica dell’urlo” viene vivisezionata e successivamente cristallizzata

in un gioco cerebrale di stop-and-go, di ossessioni e di spasmi che di

certo guarda anche al Coltrane

di “Interstellar Space”. Così, nel fluire ora pacato, ora sostenuto

delle sue meditazioni, questo flusso di coscienza “strutturato” lascia

intravedere tutto il valore dell’organizzazione del suono e del rumore

all’interno di uno spazio vuoto dove regna, sibillino, il silenzio. E,

in questo vortice di rabbia e malinconia, anche il ticchettio delle dita

sui tasti acquisisce finalmente un valore musicale; un valore che è,

innanzitutto, ritmico-strutturale, tra nuances ed esplorazioni

timbriche, sulle tracce di Helmut Lachenmann.

Con questo

bagaglio di esperienze e di soddisfazioni, in esilio in Francia come

numerosi suoi colleghi (“Andai in francia per la prima volta. Avevo un

biglietto di solo andata e cinquanta dollari”), Braxton continua a

lavorare allo sviluppo di un nuovo linguaggio improvvisativo, ricercando

un vero e proprio “metodo”, in seguito definito, nelle note di “Alto

Saxophone Improvisations” (1979), “conceptual grafting”. Sulla base di

questa sorta di rappresentazione sinestetica, che assegna a particolari

suoni determinate rappresentazioni visuali, ci si riferisce,

inizialmente, all’atto improvvisativo solo tenendo conto delle sue

“infrastrutture”, per cui vari fattori vengono isolati e resi

significativi durante l’evento musicale. Il “conceptual grafting” non ha

nulla a che fare con l’armonia di tipo convenzionale, né è previsto un

tema nel senso classico del termine. Piuttosto, esso mira a chiarire

“l’implicazione dinamica” degli elementi base (timbro, altezza, etc.).

Se questo approccio “razionalistico” o “matematico”, che dir si voglia,

sembra gelare ogni impeto passionale, tuttavia è lo stesso Braxton a

precisare che le dinamiche del suono non sono, e non devono essere!,

separate dalle sue implicazioni spirituali (che hanno a che fare,

innanzitutto, con lo stato esistenziale di un determinato momento) e

fisiche (essenzialmente, il rapporto che si viene ad instaurare tra il

musicista ed il suo strumento) – aspetti che, viene sottolineato, sono

da sempre alla base di varie culture africane ed asiatiche.

“Ok, sono nel sottosuolo, ma mi sento a casa…”

Così,

tra una partita di scacchi, una crisi depressiva e momenti di infuocato

ardore, in una Parigi resa gelida da un inverno più rigido del solito,

il 25 febbraio del ’72 il Chicagoano registra in una sola session

“Saxophone Improvisations, Series F” (conformemente al suo approccio

matematico, Braxton stabilisce per ogni tornata di improvvisazioni un

numero di serie), una delle opere musicali (ci sia concesso…) più

incredibili e lungimiranti del ‘900. Prolungamento ultimo di

innumerevoli esperimenti sul sassofono alto, l’opera eclissa tutto

l’apparato concettuale che la sostiene, dimostrando la statura

gigantesca di un musicista unico. Basta ascoltare i tre stage iniziali

della “Composition 8I” per comprendere il livello di stravolgimento

raggiunto. Lo stesso timbro dello strumento subisce una vera e propria

tortura, mentre il suono viene smembrato in micro-cellule che si

susseguono in una costruzione spastica, frammentata, che, a fragilissimi

accenti melodici, contrappone violentissimi slap-tonguing.

Gli

sconfinati orizzonti lirici di “Composition 26 A (Dedicated to

Marie–Claude Conet)” tratteggiano i primi contorni del Braxton più

meditativo e “notturno”. Un’unica linea sinuosa viene modellata con

eccelsa sapienza emotiva, con qualche piccolo brivido “vibrato” sul

finale. E’ un’immersione impareggiabile nell’anima dell’artista, alle

prese con un soliloquio che non scade mai in autismo psichico. Nella

ballata di “Composition 26 J (Dedicated to Dave, Claire and Louise

Holland”) il suono si arricchisce delle sfumature retroattive

dell’ambiente (se ne ricorderà Evan Parker per il suo “Monoceros”). Lo

sfondo sembra, contemporaneamente, annegare nel silenzio e fungere da

contenitore illimitato per l’espandersi sottilissimo delle note.

L’impronta “spaziale” del suono…l’importanza dei residui delle

tonalità che scaturiscono dalla stratificazione di suono e contesto

fisico… “E’ un’estensione del mio amore per la melodia. E’

un’estensione del mio amore per lo “spazio poetico…”.

Il primo

disco si conclude con quella che è molto probabilmente la vetta assoluta

della sua produzione “solo”: la “Composition 26 B (Dedicated to Maurice

McIntyre”). Le tremolanti note che la introducono sono repentinamente

assalite da atroci contorsioni, in un gioco ubriaco di orrore ed

euforia, per parafrasare quanto Ekkehard Jost scrisse a proposito dello

stile di Ayler. Il fiato che muta in atonali escandescenze metalliche;

il sound “cool” di Paul Desmond e le vibranti derive di Roscoe Mitchell,

convergenti in un tappeto “percussivo” e sincopato che si immerge e

riemerge da una marea montante di estasi straziata. Si ascoltano,

dunque, le note trattenute sul baratro, mentre il fiato diventa acciaio

liquido. Scorribande esasperate e mulinelli sonici si arrampicano

furibondi su se stessi, percuotendo la serie di base ed impennandosi

vertiginosamente fino al limite dell’udibile, lì dove le note rischiano

di cedere il posto ad un sibilo lancinante, pronto a dissolversi da un

momento all’altro. Si tratta di vere e proprie discese nell’ignoto, tra

slap tonguing che sono come frustate e accordi grattugiati nel metallo.

In questo continuo disintegrarsi di invenzioni, la ricodificazione della

sintassi improvvisativi del sax si scontra con quella del timbro, delle

altezze e della dinamica. Nel gioco di specchi tra “piano” e “forte”,

di spirali filiformi ed isteriche, viene eretto un edificio mostruoso,

che è palingenesi assoluta e definitiva del jazz, fatta di viscere,

sputacchi, ansimi ed abomini armonico/melodici, fino alla violenta

carrellata finale, esemplare e maniacale nel suo sconvolgimento

radicale. Innumerevoli prenderanno nota, pochi sapranno eguagliare il

maestro.

“Composition 26 D (Dedicated To Ann Taylor”) è un’altra

delle sue superbe ballate dai toni sommessi e venati di malinconia, qui

sulla scorta di un refrain tanto semplice quanto toccante. In

“Composition 8 J (Dedicated to Buckminster Fuller)”, Braxton lavora

intorno ad un pattern di 8 note, entrando ed uscendo dal recinto che di

volta in volta viene costruito. Il linguaggio preso in esame in

“Composition 26 C (Dedicated To George Conley”) rimanda, invece, al

be-bop: frasi veloci e spigolose; narrazione vorticosa, nervosa,

ondulante. Il fluire vorticoso, magmatico viene spezzato solo per

accennare brevissime frasi melodiche, il cui unico scopo, in fondo, è

quello di evidenziare la potenza “razionale” dell’intera composizione.

In ultima istanza: una pulsazione ossessiva, che trascende, in qualche

modo, il vecchio concetto di “swing”. Piccoli solchi nel silenzio. Un

silenzio nitido, frastagliato di accenti crepuscolari. Un silenzio

“fisico”: nella “Composition 26 I (Dedicated to June Patton”), il suono

lotta contro la vertigine dell’assenza. Un microscopico amplesso di

detto e non-detto, per una ballata “cerebrale” che indaga, con

discrezione, il mistero che lega il suono al suo

provenire-precipitare-svanire dal/nel nulla. “Ritornare là dove i nomi

sono di troppo”, diceva John Cage; ovvero, come precisa Daniel Charles,

“al silenzio, al regno delle evidenze… nel luogo dove nomi e cose si

fondono e sono uno: alla poesia, regno dove il nominare è essere”.

L’omaggio

a Philip Glass nella “Composition 26 F” si lancia in diciannove minuti

di reiterazioni ossessive, la cui direttrice “orizzontale” subisce

continue mutazioni, come in un isterico cardiogramma. Il minimalismo del

compositore americano viene qui esaltato nei suoi caratteri più

ipnotici. Al di là della “repetition structure”, il “processo additivo”

viene ripercorso con ardore quasi claustrofobico, permettendogli di

destrutturare, “distruggere” e ricostruire, da prospettive diverse e

convergenti, alcune figure melodiche di base, miscelando minimalismo e

be-bop stilizzati, il Coltrane più “free”, Eric Dolphy e accenti Desmond-iani.

“Dopotutto, spesso mi sento la persona più fortunata del mondo…”

Nonostante

si siano succeduti durante gli anni a venire gli esperimenti in

solitaria (in opere come, ad esempio, “Alto Saxophone Improvisations” –

la sua opera più compiuta dal punto di vista “teorico” -, “Wesleyan (12

Altosolos) 1992”, “Solo (Koln) 1978” e “Solo (Milano) 1979 vol. 1 &

2”), l’epifania di “Saxophone Improvisations, Series F” resta tutt’ora

insuperata, non solo all’interno del corpus braxtoniano. Il lascito

dell’opera è, di fatto, risultato basilare per tutti gli sviluppi

dell’improvvisazione “solo”, di ogni ambito e matrice: basti pensare a

Leroy Jenkins – violino, Albert Magelsdorff e George Lewis – trombone,

Greg Kelley – tromba, Dave Holland – violoncello e contrabbasso, Eugene

Chadbourne – chitarra, etc.. Inoltre, molte di queste intuizioni, pur

essendo vicine alle cose che Roscoe Mitchell stava facendo nei suoi

esperimenti dentro e fuori l’Art Ensemble Of Chicago a cavallo tra i

Sessanta ed i Settanta, saranno altresì fondamentali proprio per gli

sviluppi successivi della musica di Mitchell, che in opere quali

“Nonaah” e “LRG/ The Maze/ S2 Examples” percorrerà strade più

marcatamente braxtoniane nel ridefinire, ancora una volta, gli orizzonti

sperimentali della sua ricerca musicale.

Insomma, l’alba del

1972 coincide con un momento particolare nella vita di Anthony Braxton:

risiede in una città bellissima e molta calorosa con gli artisti

“incompresi”; gioca spesso a scacchi con gli amici, cercando di tenere a

bada una depressione imperante; intrattiene jam estemporanee con altri

artisti afroamericani “in esilio”.

Forse gli costò qualcosa in termini personali, ma con quest’opera ci ha regalato una pagina indelebile del suo diario personale…